What were foreign interventionists doing in Russia during a conflict which helped to define the 20th century?

© RT

One hundred years ago, on October 25, 1922, the Russian Civil War drew to a close. It was on that day that the Provisional Priamurye Government, the last anti-Bolshevik Russian state enclave, ceased to exist, in the Russian Far East.

The remnants of the White movement left Vladivostok. By that time, the territory of the former Russian Empire was almost entirely controlled by the Bolsheviks, although islands of resistance continued popping up sporadically in various parts of the country for several more years.

The Russian Civil War wasn’t similar to other such conflicts most people know. Unlike the American Civil War fought between the Northern and Southern states or the Spanish Civil War between the Francoist forces and the Republicans, the fighting in Russia was not simply a standoff between two uncompromising sides. The opponents of the Bolsheviks, which were collectively known as the ‘Whites’, were unable to present a united front against the ‘Reds’ due to discord within their own ranks. Moreover, separatists who were active on the periphery and generally leaned towards the Communists often intervened in the confrontation between the main warring groups and factions, which were the Bolsheviks, Monarchists, Februarists, Mensheviks, Socialists, Anarchists and other scattered forces adhering to various ideologies.

Read more

The theater of the Russian Civil War looked very much like a blood-covered patchwork quilt on fire, with short-lived state entities appearing now and then across the vast expanse of the country. It was an ‘all-against-all’ kind of warfare, with numerous coalitions and alliances formed and then disbanded time and again. As this was happening, however, the Bolsheviks claimed more and more Russian territory.

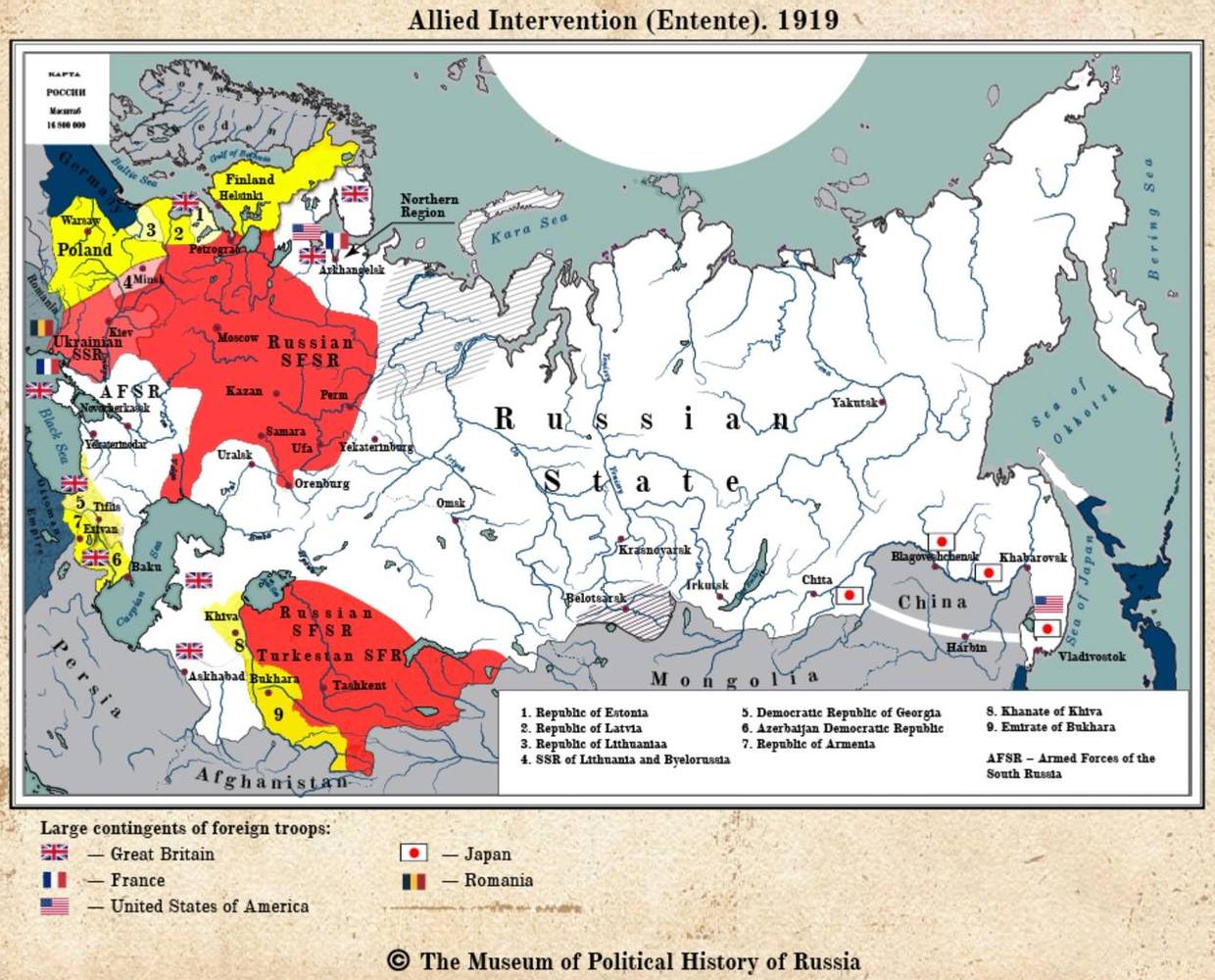

And the Allied interventions – coming from states that had previously been friendly with the Russian Empire and were even supposed to help it crush the Bolshevik regime – took place right in the middle of all that bloody chaos. But instead of supporting Tsarist Russia, their course of action ended up serving the Bolsheviks’ goals.

RT looks back at how the global community exploited the country’s weakness and, instead of trying to disrupt the formation of a state that would later evolve into one of its bitterest enemies, on the ruins of imperial Russia, did its best to facilitate the process.

It all started with foreigners

It’s probably no coincidence that the official start date of the Russian Civil War is identified by many historians as the revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion – on May 17, 1918 – even though by that time hostilities had already been going in the south for a few months.

The Czechoslovak Legion was a volunteer armed force with the Russian Imperial Army composed predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I. In the fall of 1917, the Russian Provisional Government granted the group permission to increase its force by enlisting Czech and Slovak prisoners of war and deserters from the Austro-Hungarian Army, many of whom wished to fight the Austro-Hungarian Empire for the independence of their homelands and gladly joined the Russians.

Personnel of the 1st Czechoslovakian corps listen to award ordinance. © Sputnik / Nikolai Yeronin

The decision backfired after the October Revolution ended the Provisional Government and the Bolsheviks moved to sign a separate peace treaty with the Central Powers, thus effectively undoing a lot of the Russian Empire’s achievements of the previous decades. The Czechs hurried to denounce the new revolution and declare their support for the deposed government.

Thus, formally, the Czechs turned against the Bolsheviks, but it became clear over the course of the conflict that they were primarily fighting for themselves rather than for any other cause.

Read more

First, the Czechoslovak Legion was swiftly reassigned to the command of Paris and effectively became a part of the French army. Second, one of the founders and leaders of the Legion, Tomas Masaryk, who was also the future first president of Czechoslovakia, was actively involved in negotiations with all parties to the Russian Civil War. He abstained from siding with the White movement, tried to forge a relationship with the Bolsheviks and even allowed Communist propaganda in the Legion’s units.

The Legion, which was stationed at the time on the territory of modern Ukraine, was eager to leave Russia for France, but that plan was foiled by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ceded a large chunk of the Russian Empire’s western lands, including Crimea and present-day Ukraine, to Germany. The Czechoslovak Legion had to retreat eastward in a hurry.

Masaryk decided that the Legion should travel to the Pacific port of Vladivostok and even negotiated a deal with the Bolshevik authorities. Tensions continued to mount, however, as each side distrusted the other, and ultimately the Legion had to fight its way to the Pacific along the Trans-Siberian Railway, refusing to surrender its weapons to the Reds or to deal with them in any way – until they had no choice.

Treachery of the Allies

The Czechoslovaks easily foiled all attempts to disarm them and kept capturing towns along their route. Everywhere they went, Whites from the Siberian regions joined them. Also, they were able to seize the Russian Empire’s gold reserve.

However, there were fewer and fewer battles for the Legion to take part in. By autumn, the war with Germany was over and the Czechs had won their independence – an event that, paradoxically, depleted their morale: the soldiers could think of nothing else but returning to their homeland. In 1919, they hardly did any fighting at all – instead, they went on a looting spree. As they were in control of the Trans-Siberian Railway, the Czechs would routinely stop trains, rob everyone on board and ’empty’ the train cars of refugees. This eventually earned them their nickname, ‘Czechosobaks’ (which in Russian literally means ‘Czechoslovak dogs’).

Read more

One of the victims of the Czechs’ tyranny on the railroad was the White movement’s most prominent figure, Alexander Kolchak, who had been named supreme ruler of Russia not long before. His train was repeatedly stopped by the Czechs in late 1919, until it ended up in the town of Nizhneudinsk. At that time, in the neighboring city of Irkutsk, a leftist group that included Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks established a political group called the Political Center, which demanded that Kolchak hand over power to Anton Denikin. Kolchak was then promised safe passage, but his personal guards were to be replaced by Czechoslovaks. Admiral Kolchak accepted these conditions, but that did not save him from eventually being executed. On January 15, 1920, the Czechoslovaks turned Kolchak over to the Political Center, and the Socialist-Revolutionaries threw him into prison.

After an attempt by White forces loyal to Kolchak to recapture the former supreme ruler in Irkutsk, the interventionists behind the Czechs announced that they were prepared to fire upon the Whites to prevent Kolchak from escaping. To prove that their intentions were serious, the former Entente allies disarmed several units of the White Guardsmen.

As early as January 21, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks surrendered power in Irkutsk to the Bolsheviks. The latter interrogated the admiral and sentenced him to execution by firing squad.

The handing over of Kolchak to the Bolsheviks was, in a way, the foreign legion’s ‘payment’ for a chance to safely leave Russia. With the prisoner in their custody, the Bolsheviks promptly began negotiations with the Czechoslovaks. The two sides exchanged detainees and the Central Europeans promised to return the gold reserves to the Soviets as soon the last foreign soldier left Irkutsk. In September 1920, the last servicemen of the Czechoslovak corps left Vladivostok aboard the US Army Transport ship Heffron.

Admiral Alexander Kolchak, the ‘supreme ruler of the Russian state’, at the front. © Sputnik

But that was not the end of the Czechs’ involvement in the Russian Civil War.

Aliens in Russia’s north

The need to evacuate the legion was used to justify the Western intervention after Germany’s ultimate defeat. However, foreign troops had been on Russian territory several months before the end of World War I. Ostensibly, their presence was the result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, although in actuality Russia’s ‘allies’ from the Entente had agreed on the occupation zones of the Russian Empire well before it was signed. The Bolsheviks’ peace treaty with Germany was just the catalyst to force the Allied powers to act more resolutely.

Read more

There was an attempt to justify the intervention by the need to establish an anti-German front in Russia with or without the cooperation of the Soviet government. The Allies were afraid that the Germans, who had landed in Finland, might be able to capture Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, Russia’s main northern ports, which also held military supplies.

The British reached out to the Bolsheviks and offered to land in Murmansk and take the city before the Germans could do so. In spite of the peace treaty, the Reds were indeed afraid of possible German advances, so they took London’s offer while trying to maintain secrecy and shifting the responsibility to the local authorities.

After direct threats from Germany, the Bolsheviks realized they had made a mistake, but it was too late to try to push the Brits out. In the spring of 1918, 1,500 British troops were stationed in Russia’s north.

The subsequent landing of 9,000 more servicemen in Arkhangelsk was not coordinated with the Bolsheviks at all. Apart from the British, soldiers from other countries, including Italians, Serbs, and Americans, were involved in the operation.

Invaders enter Arkhangelsk, 1918. © Sputnik

The Red Army was helpless to thwart the landing and simply withdrew from the city before the Allied forces arrived. Enemies of the Bolshevik government led by Captain 2nd Rank Chaplin tried to exploit the situation, but, much to their disappointment, the British had their own plans for Arkhangelsk. They installed a leftist government headed by Nikolai Tchaikovsky, an English socialist with a long track record of socialist agitation.

The local officers were not pleased by such a turn of events, so they orchestrated a coup in September 1918 and arrested the leftwing politicians. The British intervened by freeing all of those who were jailed and removing the conspirators from Arkhangelsk.

Anti-Bolshevik forces in the sparsely populated northern regions lacked resources and struggled to feed their armies so, consequently, they had to depend on the interventionists, who had no intention of helping the Whites topple the Reds.

Read more

Foreign troops spent the whole of 1918 stationed in Murmansk and Arkhangelsk without making any serious attempts at major inroads beyond pushing a few kilometers inside Russian territory.

After the end of World War I, even the Allied powers themselves had trouble figuring out what they were still doing in Russia, given that they were not actively fighting the Bolsheviks and lacked the power to do so. By 1919, the Red Army had become a formidable force that a few thousand foreign soldiers were no match for.

Ultimately, in September of that year, the Allied powers simply boarded their ships and left the region.

Americans in Siberia

The intervention was much more active in the eastern part of Russia, through which the country’s main transport artery, the Trans-Siberian Railway, passed.

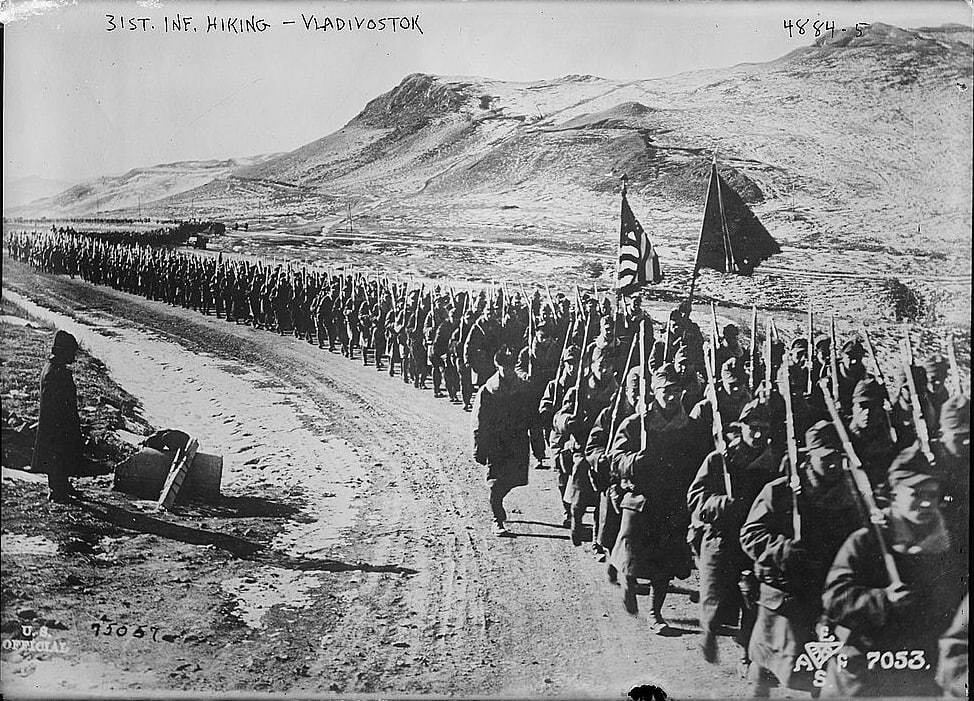

The Americans landed an expeditionary force dubbed ‘Siberia’ consisting of about 8,000 troops in Vladivostok in August of 1918. They immediately declared that they were completely neutral and gave assurances that they would not interfere in Russia’s internal affairs or provide support to either the Whites or Reds. While the British in the north were still engaging in political intrigues, the Americans claimed to be simply guarding the railway.

American soldiers from the 31st Infantry marching near Vladivostok Russia. © Wikipedia

Perhaps the American mission would have been less upsetting for the locals had it not been headed by General William Graves, for whom the word ‘monarchist’ was a terrible curse word. Having no understanding of the local situation at all, he thought the Bolsheviks were something akin to America’s Founding Fathers and that they were fighting for freedom against tyranny, while he considered all Whites to be monarchists.

As a result, Graves sympathized with the Bolsheviks and put spokes in the wheels of the Whites. His relations with the latter’s officers, who could see the American general’s actual deeds, were very strained. For example, in the fall of 1919, he blocked a shipment of weapons bought by Whites on the grounds that they allegedly wanted to attack him.

Read more

The manager of affairs in the Kolchak government, Georgy Gens, observed:

“In the Far East, the American expeditionary forces behaved in such a way that anti-Bolshevik circles became convinced that the United States did not want to see the triumph, but rather the defeat of the anti-Bolshevik government. They expressed sympathy for the partisans, as if encouraging them to take further action.”

In his opinion, “It was clear that the United States did not realize what the Bolsheviks were, and that the American general, Graves, was acting according to certain instructions.”

Another White leader, Ataman Grigory Semenov, recalled:

“Almost all the weapons and uniforms coming from America were transferred from Irkutsk to the Red partisans, and General Graves, an ardent opponent of the Omsk government, knew about this. The conduct of the Americans in Siberia was so hideous from a moral point of view and just in terms of basic decency that the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Omsk government, Sukin, being a great Americanophile, could barely hush up the scandal that had begun to erupt.”

Ataman G. M. Semenov with representatives of the American mission headed by W. Graves. Vladivostok. © Wikipedia

The Canadians also took a symbolic part in the intervention in Siberia. As subjects of the British crown, they sent a small expeditionary force, which mainly carried out police service in Vladivostok. It stayed in Russia for only six months before returning home in the spring of 1919.

Japanese adventurism

Read more

The only participant in the intervention that approached the issue in a serious way was Japan. According to various estimates, its army in the Russian Far East was 30,000-70,000-strong. In terms of numbers, the Japanese forces significantly outnumbered all of the other Allied contingents combined. In addition, the Japanese were the most adamant in insisting on the intervention – and they were also the last to leave. They were the only Allied country to take active part in actually fighting the local partisans themselves.

However, Tokyo clearly hoped to snatch some of Russia’s territory, or at least create a pro-Japanese buffer state in the Far East.

For this reason, the allies had to constantly pull Tokyo back and tame its ambitions. The Japanese placed their hopes in Ataman Semenov, who could only be classified as ‘White’ because his detachments were fighting the Bolsheviks.

Unlike the Whites in the north and Siberia, who had to buy weapons and ammunition from the Allies (often even defective ones), Semenov received weapons from the Japanese in large quantities for nothing.

Unlike the rest of the Allied forces, which were either engaged in protecting the Trans-Siberian Railway or sitting in port cities without sticking their noses out, the Japanese occupied a significant chunk of the eastern territories, holding all of the larger cities east of Chita by the fall of 1918. With the military support of the Japanese, Semenov’s detachment managed to capture the area of Transbaikalia.

At the same time, the Japanese clearly did not seek to unite with the White forces in order to defeat the Bolsheviks. While they supported Semenov, they were extremely hostile to Kolchak. This animosity also manifested itself in their relations with the Russian commanders. One witness to the Civil War in Siberia, the Latvian writer Arved Shvabe, noted:

“Sometimes, the Japanese approved territorial uprisings directed against Kolchak in order to weaken his position.”

By the beginning of 1920, all of the Allied expeditionary forces had withdrawn from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). Only the Japanese remained, hoping they could still get something for their trouble. In order to rid themselves of the Japanese, the Bolsheviks turned to a diplomatic trick. A significant part of the region was proclaimed to be a completely independent state called the Far Eastern Republic (FER), which was not designated as a socialist state. In fact, Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks worked side by side with the Bolsheviks in local government there.

So, it turned out the Japanese were no longer occupying Russian land but rather an independent and neutral Far Eastern Republic, which, de jure, was not even a Soviet state. This made it twice as hard for the Japanese to justify their presence there, as they were under a lot of pressure from their allies, especially the Americans.

Under diplomatic pressure, the Japanese recognized the FER and left its territory. At this point, Vladivostok and the north of Sakhalin were the last places still occupied by the Japanese, who were already in diplomatic isolation. In 1922, Tokyo began to evacuate its troops from Vladivostok.

Japanese officers in Vladivostok with local commander Lieutenant-General Rozanov. © Wikipedia

Two weeks later, the Far Eastern Republic announced its accession to the RSFSR. Having fulfilled its mission, there was no further reason for its existence.

***

The intervention had ended with the White movement harmed while the Reds were assisted. The Bolsheviks instantly turned into defenders of the Revolution and patriots fighting imperialists (though there were practically none to fight). This greatly facilitated propaganda against the Whites, who were forced to tolerate allies who had been harming Russia.

The interventionists had never set out to overthrow the Bolsheviks and did not fight the Reds. The military contingents these ‘allies’ sent to Russia were miniscule. According to the most optimistic estimates, the number of interventionists, not counting the Japanese, did not exceed 30,000 troops. Against the 5-million-strong Bolshevik army, this was less than a drop in the bucket.

By Georgiy Berezovsky, Vladikavkaz-based journalist