Official Kiev has been talking about an alleged “genocide of Ukrainians by Russia” for more than 30 years. What’s wrong with this myth?

© RT / RT

At the end of November, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the great Soviet famine of the 1930s. According to different estimates, the tragedy claimed from four to nine million lives throughout the country – in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine.

The exact number of deaths is hard to determine due to a lack of records, but the general Western consensus is that most deaths happened in the Russian and Ukrainian republics, with slightly more overall in the latter. However, per capita, the biggest effect was in Kazakhstan (where it is called the Asharshylyk), which lost over a third of its entire population.

From the very first years of Ukraine’s independence, this event – known as the Holodomor (death by hunger) in the Ukrainian language – was politicized and served as a basis for constructing the country’s new national identity.

For decades, various Ukrainian politicians, and other opinion formers, have convinced their people that the starvation of the 1930s was a deliberate and cynical extermination of the country’s intelligentsia and peasantry. Perpetrated by “Russians.”

However, not only was the Soviet Union controlled by the Georgian Joseph Stalin, at the time, Russians also died in their millions during the horrific great hunger.

Read more

Cutting ties with the Empire

Since the end of the 19th century, Ukraine has attempted to nationalize and mythologize its history in order to create a distinct Ukrainian national identity. For example Mikhail Grushevsky’s concept that Ukraine is the direct successor of Kievan Rus. In the post-Soviet period, the tendency to mythologize history grew even stronger in the new state. Backed by the government, Ukrainian researchers created their own historical narrative, attempting to separate the country’s history not only from its Soviet but also from its imperial past.

Modern Russia was considered an ‘heir’ of the Soviet Union and of the Russian Empire – in Ukraine’s understanding, the “colonizers” who wanted to wipe out the country’s national identity. Kiev quickly assumed the role of a victim of the communist regime. This allowed the country’s authorities to cut themselves off from the controversial decisions of the Soviet era – for example, the policy of “korenizatsiia” (nativization) i.e. the forceful “Ukrainization” of the republic’s elites and its cultural and educational fields. Most importantly, this concept allowed Ukraine to blame someone else for the country’s modern-day problems.

The narrative implied that the main tragedy of the Ukrainian people in the Soviet era was not World War II and the German occupation, but the great famine of the 1930s. According to various estimates, between 3.5 million and 10 million people died of hunger throughout the USSR at that time. But in independent Ukraine, these tragic events were presented as a deliberate genocide against the peasantry and the intelligentsia. The tragedy became known as the Holodomor (literally death by hunger).

According to the conclusions made by the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the famine was the result of a policy of forced collectivization that was implemented throughout the USSR. The censuses of 1926 and 1937 indicate that some other Soviet regions suffered from the famine, per capita, even more than the Ukrainian SSR. For example, the population of Ukraine decreased by 20.5% while that of Kazakhstan decreased by 30.9%, and the population decline in Russia’s Volga Region amounted to 23%.

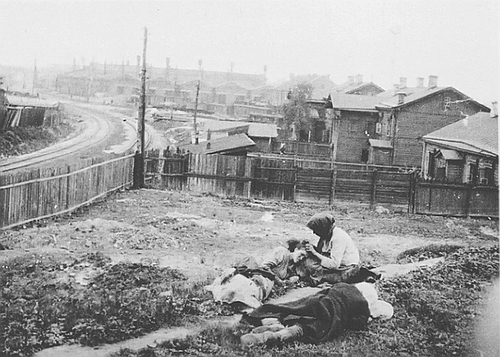

FILE PHOTO. Starving Ukrainian peasants. © Wikipedia

However, Ukrainian historians chose to ignore the data and insisted that the famine affected only Ukraine and, moreover, was a deliberate plan to annihilate the Ukrainian population. The Holodomor was widely discussed in the late 1980s, in light of the increasing criticism of communism. It played a major role in legitimizing Ukraine’s secession from the USSR and was actively used for propaganda purposes. Before the independence referendum, Ukrainian TV broadcast a publicly funded documentary film about the 1930s famine.

The Ukrainian diaspora abroad played a major role in presenting the Holodomor as a deliberate extermination of Ukrainian people. In 1985, through the efforts of an organization called Americans for Human Rights in Ukraine, a parliamentary commission was established in the United States to investigate the circumstances of the great famine. In 1988, the World Congress of Free Ukrainians helped establish an international legal commission that recognized the policies of collectivization, “dekulakization” (repressions against ‘kulaks’ or wealthy peasants), and starvation as acts of deliberate genocide against the Ukrainian people by the Soviet government. Ukrainian organizations also sponsored memorial exhibitions and rallies in cities and villages that had been particularly affected by the hunger.

Read more

Gradually, domestic public organizations joined the information campaign. Among these were the Rukh nationalist movement, the Union of Writers of Ukraine, and many others. The Memorial Society helped organize conferences in different regions of Ukraine – at these gatherings, the famine was discussed and eyewitness accounts were gathered. Based on this information, the book ‘Famine ‘33: National Memorial Book’ was published in 1991.

Maxim Semenov, a political analyst and specialist in the history of modern Ukraine, believes that the Ukrainian authorities turned to the topic of the Holodomor because they recognized the fragile state of Ukraine’s “independence,” its major economic dependence on Russia, and the cultural proximity of the two countries.

“Ukrainian leaders understood that over time, after overcoming the problems of the ‘90s, Russia would restore its position in the post-Soviet space. And then, it would be able to return Ukraine into its zone of influence and even create the necessary conditions for the reunification of the two countries. Therefore, in order to preserve Ukraine’s independence, it was necessary to form an image of Russia as an enemy, an enemy that has oppressed and offended Ukrainians for centuries,” he said in an interview with RT.

According to Semenov, Ukrainian propagandists presented the Holodomor as a deliberate genocide against Ukrainians, organized by the Soviet government in the Ukrainian SSR. This propaganda was spread by means of the media, school history textbooks, public events, and in many other ways. Moreover, the Ukrainian authorities emphasized two things: that the famine was man-made, and that its sole aim was to kill Ukrainians.

“Obviously, this does not match historical facts, but that does not bother Ukrainian propagandists. As a result of the systematic work carried out through the media, the public education system, and culture, and by implementing the politics of memory, for over 20 years the Holodomor has been one of the key themes [in Ukrainian politics],” Semenov says.

FILE PHOTO. People light candles in memory of the victims of the Holodomor famine during a ceremony at the Holodomor memorial in Kiev on November 26, 2016. © SERGEI SUPINSKY / AFP

“As the successor of the USSR, Russia was presented as a historical enemy that allegedly always wanted to annihilate Ukrainians, that starved them to death and so on. As Ukrainian propagandists explained, grain was taken from Ukrainian peasants and exported to the RSFSR – in other words, Russians lived at the expense of the dying Ukrainian peasants. Moreover, in the 2000s, the gap in the standard of living in Russia and Ukraine became apparent. Ukrainians lived in objectively worse conditions and this created the impression that Russians continued to prosper while the people of Ukraine suffered,” the political analyst adds.

Semenov emphasizes that Ukraine’s official historical narrative is based on the belief that “Ukrainians were betrayed, offended, oppressed.”

Read more

“All this, of course, prepared the population for war. Ukrainians [were told that they] will have to defend their independence from ‘the terrible Russia that will come, capture, and starve you again.’ Of course, one cannot construct a national identity on a single [historical] episode, but the shared tragedy and past suffering united millions of Ukrainians,” Semenov says.

New history

Ukraine’s first president, Leonid Kravchuk, was determined to retain power by any means and, in light of rising nationalism, the easiest way to do so was by denying Ukraine’s Soviet legacy. Moreover, it helped distract the population from major economic problems. That is when the subject of the Holodomor came in handy.

Kravchuk supported the official perpetuation and commemoration of the 1930s famine. In 1993, he issued a decree “On the events related to the 60th anniversary of the Holodomor in Ukraine,” and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs became determined to have the famine added to the list of commemorations observed by UNESCO. In the same year, the president took part in an international conference dedicated to the Holodomor tragedy, where he stated that the famine was directly initiated by Moscow as a genocide against the Ukrainian people.

The president was assisted by Ukrainian nationalists. The Association of Famine-Genocide Researchers demanded the creation of a parliamentary commission that would investigate the circumstances of the tragedy. Former dissident Levko Lukyanenko wanted communist officials “involved in organizing the famine” to be tried at the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian Parliament) Nikolay Zhulinsky also attempted to hold parliamentary hearings on the subject, but failed – at the time, the faction of the Ukrainian Communist Party held a majority of seats, as many deputies retained their posts since Soviet times. The idea was also resisted by the authorities in Ukraine’s southeast regions, which have always taken a pro-Russian stance.

FILE PHOTO. Young ultra-nationalists carry placard reading “1933. Remember – means to fight” during their march in memory of the victims of the Holodomor famine in western Ukrainian city of Lviv on November 29, 2013. © YURIY DYACHYSHYN / AFP

The socio-economic crisis that broke out in the country temporarily pushed the Holodomor theme aside. In 1993, hyperinflation, rising unemployment, and the closure of production facilities worried Ukrainian people a lot more than historical issues. However, under Kravchuk, the Holodomor theme gained a strong foothold in Ukraine’s academic and legal circles, and became one of the staples of the national identity policy.

Ukraine’s second president, Leonid Kuchma, addressed the subject with caution, mainly during political confrontations with nationalist and pro-Western forces. Before the 1998 parliamentary elections, he issued a decree on holding commemorative events related to the 65th anniversary of the events of the 1930s, and also established a memorial day to honor the victims.

Read more

In 2002, at the height of the “Rise, Ukraine” anti-presidential protests, Kuchma also initiated commemorative events and suggested erecting a memorial in Kiev to the victims of the Holodomor and political repressions. However, the decree was never carried out. A year later, in 2003, Kuchma’s supporters in the Rada were able to seize the initiative and proposed holding parliamentary hearings which were first discussed during Kravchuk’s presidency.

At the hearings, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Tabachnik called the Holodomor a great demographic and social disaster that affected modern-day Ukrainian society, preventing economic growth and the establishment of democracy. Three months later, the Rada held a meeting to approve the text of a special address to the nation. In this document, the famine was called a Stalinist genocide against Ukrainians and one of the largest acts of genocide in history. It also called on the world community to recognize this historical narrative.

By the early 2000s, the idea of the Holodomor as an intentional genocide was accepted at state level. Politicians weren’t solely responsible for this – on the contrary, their policy at the time was quite inconsistent. But the subject of the annihilation of the Ukrainian people was consonant with the country’s growing national identity and society itself took up the initiative.

Between the Maidans

Ukraine’s third president, Viktor Yushchenko, was the one who most often resorted to the theme of genocide in the politics of memory and national identity.

Yushchenko issued a new decree on perpetuating the memory of Holodomor victims. It implied providing financial assistance to the survivors of the famine, collecting materials for the National Memorial Book of Victims, and persuading the international community to legally assess the famine as genocide. The government also planned to allocate funds for erecting monuments to the victims, and to give grants to researchers studying the tragic event. The Ukrainian Institute of National Memory was also established at that time.

In 2006, Yushchenko proposed a bill that recognized the famine as an act of genocide and imposed administrative liability for denying this version of events. However, the opposition – which formed a majority in the parliament and was headed by Viktor Yanukovich – was strongly against the bill. Fearing that the original document may lead to the decline of relations with Russia, the parliament adopted a compromise version of the law. The events were recognized as genocide – though not specifically against the Ukrainian people but against the citizens of the USSR in general – and the mention of legal punishment for challenging this narrative was removed.

FILE PHOTO. Former Ukrainian President Victor Yushchenko addresses the 63rd annual session of the United Nations General Assembly at UN Headquarters September 24, 2008 in New York City. © Jeff Zelevansky/Getty Images

However, the president was determined to maintain his political course. In 2007, he proposed an alternative bill that equated the Holodomor with the Holocaust, and considered the denial of either a criminal offense. Despite being backed by the Yulia Timoshenko bloc, the parliament once again failed to pass the bill. It was finally adopted – though in an amended state – only after the new parliamentary elections, when Yushchenko’s supporters formed a stable majority in the Rada. This time, the document mentioned criminal liability for the denial of the genocide but there were no references either to the Holocaust or the Holodomor.

The president of Ukraine did not stop at legislative measures, however. In 2007-2008, he launched a major ideological campaign that extended beyond Ukraine to the international community. 2008 was declared the Year of Remembrance of Holodomor Victims, and a campaign was launched titled “Ukraine remembers – the world recognizes.” Within its framework, major memorial events – such as “Light a Candle” and “Unquenchable Candle” – were held across the nation. The Candle of Memory monument was erected at the site of the Memorial Museum of Holodomor Victims, which had been built under Yushchenko. The government continued to fund research, public rallies, exhibitions, and student projects dedicated to the Holodomor.

Read more

Yushchenko raised the topic of the Holodomor on almost every trip abroad, including in his speeches addressed to the US Congress and the European Parliament. A special working group was created in Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its task was to spread information about the Holodomor worldwide through Ukrainian embassies, with the assistance of the diaspora. As a result, the parliaments of 13 countries, including the USA, Canada, Italy, Poland and Hungary, recognized the Holodomor as the genocide of Ukrainians. However, the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly and the European Parliament refused to classify the famine of the 1930s as deliberate annihilation of the Ukrainian people.

Yanukovich, who replaced Yushchenko as president in 2010, tried to distance himself from the views of his predecessor. He discontinued the operation of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, and official websites that described the Holodomor no longer mentioned any Russian responsibility for the events. At the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) meeting, Yanukovich said the famine had been a common tragedy of the Soviet people, and not a genocide against Ukrainians. The commemorative events that took place during this time were organized by the public.

In general, Yanukovich didn’t undertake any active efforts regarding the politics of memory. He tried to maneuver between the pro-Russian southeast regions and the nationalist-minded western regions of Ukraine, which eventually resulted in the Euromaidan and a coup d’etat. Moreover, the fourth president of Ukraine was in office for only four years, while the idea of the famine as ‘genocide’ had been imposed on Ukrainians for almost three decades prior to that, and more than one generation of Ukrainians was raised on such beliefs. That’s why the country’s new authorities began to exploit the Holodomor theme with renewed vigor.

An innovative approach

During Pyotr Poroshenko’s presidency, Ukraine lost Crimea and almost lost Donbass. Therefore, the demonization of Russia as a long-time oppressor once again became relevant for forming a national Ukrainian identity. In his striving to further politicize the 1930s famine, Poroshenko came up with an innovative approach – he linked the historic events with the modern-day situation. Poroshenko equated the 20th-century famine with the war in Donbass and stated that Russia had always wanted to wipe out Ukraine, and only the means have changed.

Read more

This policy was immediately confirmed at the legislative level, and this time successfully. Poroshenko issued a special decree obliging the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences to study the circumstances of the famine, and most importantly, to find people who were involved in organizing it. Moreover, the decree provided budgetary funds for public initiatives related to perpetuating the memory of the victims. Just like Kravchuk and Kuchma before him, Ukraine’s fifth president turned to the themes of the famine and the struggle against the ‘destructive legacy of Soviet power’ to explain the country’s modern-day problems. But, unlike his predecessors, Poroshenko was fully backed by a loyal parliament and government.

In 2016, the Rada again appealed to the international community to recognize the famine as a deliberate genocide against Ukrainians, but the emphasis was shifted towards the current political situation. The document stated that the recognition of the genocide would aid Ukraine in the fight against “the aggression of Stalin’s followers from the Kremlin.” Poroshenko even personally asked Western leaders to side with him, and Portugal became Ukraine’s first ally, in this regard, in 2017.

Same old story

Despite the fact that, during the 2019 presidential elections, Vladimir Zelensky presented himself as the antagonist of Pyotr Poroshenko in ideological matters, he continued to exploit the Holodomor theme as well. Shortly after coming to power, Zelensky announced the opening of a museum dedicated to the “Holodomor genocide.” In his speech, he accused the “Stalinist regime” of “purposefully annihilating” the Ukrainian people. “The project of the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide is very important for Ukraine – for our history and future. How can one strive to annihilate an entire nation? Why and what for? We will never be able to understand it. We will never be able to forget it. We will never be able to forgive it,” Zelensky said.

The Ukrainian president also continued persuading the international community to recognize the Holodomor as a genocide against Ukrainians. During his presidency, the parliaments of 15 more countries adopted resolutions recognizing the Holodomor as genocide. However, Zelensky’s Holodomor rhetoric peaked during discussions of the so-called “grain deal,” which allowed the foodstuff to be exported from Ukrainian ports.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. © Presidency of Ukraine/Getty Images

Both the Ukrainian president and other high-ranking officials (such as Prime Minister Denis Shmygal and the Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine Andrey Yermak) said Russia wanted to repeat the Holodomor on a global scale and in order to prevent this, the “grain deal” had to be extended.

Currently, Ukraine faces many other pressing issues and other means of consolidating the nation. However, making use of the ‘Holodomor theme’ and constructing the politics of memory around the famine of the 1930s remains a major aspect of Ukrainian politics.

***

Read more

Over the years, the country’s politicians have made Ukraine look like a victim that suffered first from the imperial oppression of St. Petersburg and then that of Moscow. This allowed them to separate the Ukrainian national identity from the Russian one despite the overwhelming ethnic, cultural and historical unity of the two countries.

According to political analyst Maxim Semenov, each president of Ukraine exploited the Holodomor theme to a various extent. The pro-Western presidents Yushchenko, Poroshenko, and Zelensky and the supposedly pro-Russian Yanukovych all had something in common.

“They were all Ukrainian presidents and acted as leaders of the emerging Ukrainian nation which viewed Russia and Russians as enemies or, at best, potentially dangerous neighbors. All of them exploited the topic of the atrocities that were allegedly carried out by Russia, supported Russophobic myths, twisted historical facts, and so on,” he says.

Semenov notes that, even though Ukrainian identity is not built exclusively around the tragedy of the Holodomor, it definitely holds a prominent place in Ukraine’s historical narrative – and today, a “proper Ukrainian” cannot help but grieve over the “Holodomor tragedy and yet another crime committed by Moscow.”

“However, the devastating and tragic events happening in Ukraine today have a lot more impact on forming the Ukrainian identity than the events of 90 years ago. They happen every day and every Ukrainian comes in contact with them in one way or another. Therefore, the Holodomor theme is used as a historical reference point and yet another reason why Ukrainians should fight against Russians,” says Semenov.

By Dmitry Plotnikov, a political journalist exploring the history and current events of ex-Soviet states