How do mobilized soldiers feel about the war, their enemy, and civilian life?

RT

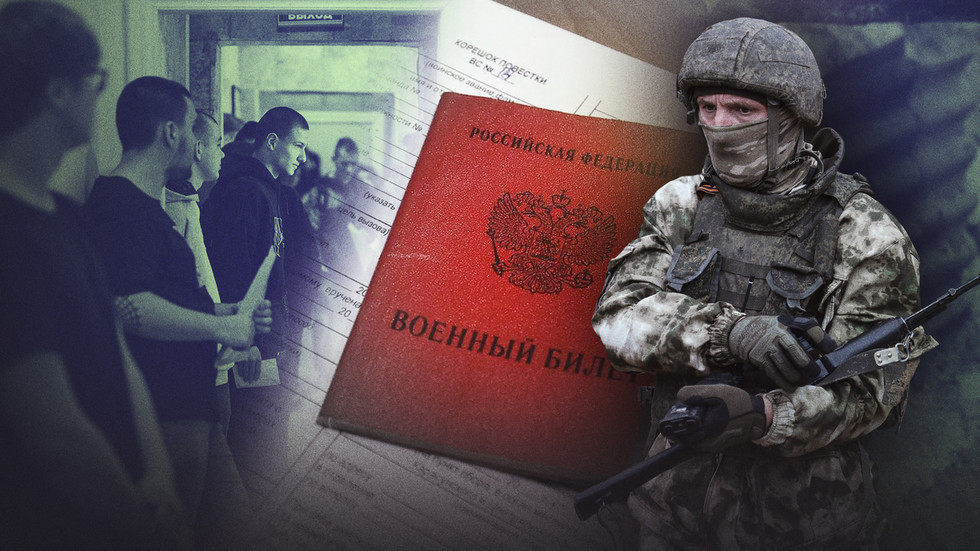

Almost a year has passed since partial mobilization was announced in Russia. In September of last year, around 300,000 men were called to the front. Although all of them had previously done their army service, they were ordinary workers, office clerks, managers, and businessmen before being conscripted. A soldier with the military call sign ‘Ural’, who used to work in the entertainment industry, was one of the first to receive a military summons.

In an interview with RT, he talked about how he and his fellow soldiers accepted the challenge to take up arms, the difference between conscripts from Russia and Ukraine, what happens to someone who switches from a civilian lifestyle to a military one, and what Russian soldiers are fighting for.

Read more

“If they call me up, so be it”

RT: How did you feel when you found out about the mobilization?

Ural: About a week before the mobilization was announced, I started thinking that this might happen soon. Things like changes in legislation, the consideration of draft laws on desertion, etc., naturally gave rise to such thoughts. I immediately thought that this is where things were going.

Of course, I was worried to a certain extent because it was unclear what this would all lead to, how big the mobilization would be. It wasn’t clear whether we were expecting a total mobilization or a partial one, as it turned out to be. I was in a state of uncertainty, so to speak.

RT: How did you react when you received the summons? Did you want to leave Russia in the interim between hearing about the mobilization and receiving the summons?

Ural: Actually, I even had the option to do so, but no, I didn’t leave. As the time of the mobilization announcement approached, I became convinced, “If they call me up, so be it. It means I’m needed. And if I’m not needed, they won’t call me up.” So when the president announced the start of the mobilization, I had already decided “come what may.” On the second day, it turned out that I was drafted into the army.

RT: After all the time you’ve spent at the front, how do you feel about people who decided to leave the country before receiving a summons?

Ural: My attitude is twofold. On the one hand, I understand that everyone chooses their own fate. We’re all adults, and we understand. But, on the other hand, this is a situation where some people were, so to speak, nurtured by their Motherland but chose to simply abandon their country. These people may be considered cosmopolitans to a certain extent. They were not interested in the fate of their country or what would become of it, so they left. It’s their choice.

Read more

“The river became an insurmountable obstacle”

RT: Which section of the front were you sent to after being conscripted?

Ural: It was the Kherson area, which is rather particular in the sense that it is divided by the wonderful Dnieper river. We did not have direct contact with the enemy during our entire time there, since we crossed the border shortly before troops were withdrawn from Kherson. After that, the fighting there stopped. There was no direct contact with the enemy in the Kherson area during that entire time. The Dnieper river was an excellent ‘demarcation line’, wide enough to prevent any direct clashes.

RT: You mentioned that you got to the front shortly before the Russian Armed Forces withdrew from Kherson. What did you think of this retreat?

Ural: There were two aspects to it. On the one hand, all of us more or less understood that this strategic decision was necessary in order to transfer a combat-ready group to another direction where it could operate.

But at the same time, there was a certain resentment because many guys remained on the other side of the Dnieper. This resentment was mostly noticeable among the professional fighters serving under contract. But, over time, many people realized that this was a necessary step, no matter how frustrating it seemed at that moment. The section of the front was stabilized and the units that withdrew from the left bank went to work in other areas.

Read more

RT: In general, did the combat situation change much after the Russian Armed Forces left the left bank?

Ural: Before the withdrawal of troops, the fighting on that side of the Dnieper seriously intensified. There was an issue with supply routes. Even now, having departed from that bank, the issue hasn’t been fully resolved. At the time, it was even more serious.

All the battles in the Kherson area have now turned into a kind of ‘Great Stand on the Ugra’ (the historical standoff between the Russian and Great Horde armies at the end of the 15th century, during which the opposing armies, standing on opposite banks of the Ugra River, did not enter into battle – RT). Of course, the artillery is active on both sides. There are also occasional attempts to transfer sabotage groups to the other side. But still, there is no significant activity here, as it was before the retreat from Kherson.

There have been attempts to cross the river, but they mostly failed. It is nearly impossible to force your way across a large river like the Dnieper in modern conditions, when only small groups are involved and not large-scale armies as it was during WWII. In a certain sense, the river has become an insurmountable obstacle for the enemy.

Read more

“People get used to everything”

RT: What sentiments prevailed among fellow conscripts when they first got to the front?

Ural: In the beginning, of course, there were mixed feelings. Most of us led a civilian lifestyle for many years. Of course, there were guys who just got out of the army, but there were also those who were demobilized more than ten years ago. These were accomplished people in their own fields. But, for many years, they’ve been far from any kind of military or army life with its strict rules. However, these people went to serve because their country called them up.

In the beginning, we were worried because things developed so quickly. Of course, when a person has to adapt from civilian to army life, the process leaves its imprint. But, gradually, people got used to it. Everyone got used to the new environment, and everyone does their job well.

RT: How long did it take you to adapt?

Ural: It’s hard to say … I’d say two or three months. During this time, people got used to the new conditions. There was physical training, so many people had to adapt. People get used to everything, but it takes time. Naturally, in addition to the physiological changes and the newly-acquired practical skills, your mindset also shifts from civilian to military mode.

Read more

“We are mostly fighting against ourselves”

RT: Do you and your fellow fighters think about the war and the enemy differently now that you’ve spent considerable time at the front?

Ural: No, not in a major way. In general, Russian soldiers are divided into two “camps” regarding their attitude towards the enemy: the people who believe they are fighting fascism and treat Ukrainians as fascists and those who believe that this is a war against a fraternal nation – a nation that has been brainwashed by Western governments. For the latter group, this is a civil war.

Personally, I share the second point of view. It’s hard to argue here, because we basically have the same guys over on the other side, especially now that the number of Ukrainian conscripts has significantly increased. These are the same people who speak Russian and have more or less the same mentality that we do.

We are mostly fighting against ourselves. Except that the other side is much more ideologically brainwashed. Moreover, this brainwashing is so severe that people do not understand what they are doing.

RT: Has the growing number of conscripts affected the combat capability of the Armed Forces of Ukraine?

Ural: I would say yes, it did. When many civilians are mobilized, this generally reduces the combat capability of the army, although we have not had direct clashes with them. Such people may not be able to cope with the task due to a lack of training and motivation. Generally, Ukrainians demonstrate a much lower level of interest in what they do and how they fight. I mean that, ideologically speaking, Russian conscripts are a lot more motivated than their Ukrainian counterparts.

Read more

RT: Does this mean that some of the conscripted Russians have become fully combat-ready?

Ural: It’s now been quite a long time [since the mobilization was announced]. We’ve had fall, winter, and spring [to prepare]. Through all this time, we were engaged in military training, shooting practice, tactical and medical training. We didn’t just sit idle, we trained and gained experience. As a result, we’ve acquired some hands-on experience.

“We are defending the life we had before the war”

RT: In your opinion, how easy will it be for people to return from the war, integrate back into society, and get back to peaceful civilian life? Will this be more difficult for the conscripts than for the professionals serving under contract?

Ural: I think it will be somewhat easier for the conscripts because we’re usually involved in the second and third lines of defense. For the most part, conscripts are not engaged in “constant assaults.” Our command uses us as a kind of “safety rope” for the regular units.

But, in any case, we now have a certain background which will, in one way or another, influence our worldview when we get back home. But I think it will still be easier for the conscripts, because we were originally civilians. So, when we get back home, it will be easier for us to return to normal life, compared to the professional soldiers.

Read more

RT: Do you think that the return of many veterans will change Russia?

Ural: I think there will be some changes. We should expect something similar to the aftermath of the campaigns in Chechnya. These people form a certain stratum of society, their own ‘brotherhood of war’. They will have a slightly different belief system. There will be a certain reassessment of values. Generally, this is already visible among the soldiers who are on temporary leave. When these people come home, they see what is going on in civilian life, which is also changing somehow. They see it and in some way have to face it. As a result, a certain transformation happens within them that’s not just about values, but about their general outlook on life.

Moreover, these people ask themselves what could be done to change their homeland for the better – both in individual households and in the entire country. I think this is a positive trend. Because the people at the front are mostly great patriots of their country and over time, their beliefs will only grow stronger. So I personally believe we will see deeply positive changes.

RT: What about you – did this combat experience change you?

Ural: That’s a difficult question because, as a rule, we don’t notice the changes within ourselves, even after a while. These changes occur gradually, not instantly. So, usually, you don’t notice them. But probably I’ve come to regard certain things in a more serious way. I began appreciating my home a lot more, including my family, friends, and regular life.

At war, you start looking at things differently. You come to understand that, among other things, you’re defending the life you had up to now – the life you had before the war, the mobilization, and everything else. You’re defending your regular, peaceful life and, as I said earlier, you appreciate that life a lot more.

By Dmitry Plotnikov, a political journalist exploring the history and current events of ex-Soviet states