The military offensive has inspired a new generation of artists

Russian gunners fire at AFU positions with Msta-B 152-mm howitzers in the Lugansk People’s Republic amid the Special Military Operation. © Sputnik/Viktor Antonyuk

While the international media focuses on the battlefield, Russia’s military operation in Ukraine is having a broader effect domestically. Another “front” has opened in the cultural sphere, and this will have long term consequences.

Poets, artists, and singers from all walks of life have embraced the realities of the conflict. An interesting factor has been how artistic techniques that the ‘liberal intellectuals’ once viewed as their own are now being adopted by patriotic voices: from high literary genres to satire and short poignant poems.

We are witnessing a return of World War II agitprop-style verses and a resurgence of long narrative poems and epics to Russian poetry tradition.

Read more

And it’s not just Russians who are charging to the cultural frontline, but Ukrainians, too – both those who reject Moscow and also others who support Russia and are willing to speak up in defense of their convictions.

Words and bayonets

Historically, the Russian poetic tradition provided a rich commentary on war. Alexander Pushkin, a contemporary of Napoleon and a witness to his aggression against the country, sang the praises of rifles and bayonets and celebrated the military genius of Russia’s general staff.

Writer and poet Mikhail Lermontov, who served as lieutenant in the Imperial Russian Armed Forces, wrote about the glorious battles of the past and his own experiences in combat.

Sergei Yesenin, Nikolai Gumilyov and futurist Velimir Khlebnikov all fought in World War I, later turning the dirt and dust of trench warfare into brilliant verses and poems.

Alexander Pushkin; Mikhail Lermontov; Nikolay Gumilyov. © Getty Images; Wikipedia

Throughout World War II, poetry served as a means of sustaining morale. A single poem could lift the spirits more than all the propaganda posters and leaflets combined. In fact, one frontline soldier said he believed that Konstantin Simonov’s composition “Kill Him!” was worthy of the Hero of the Soviet Union medal, for it alone had taken out more Nazis than the world’s deadliest sniper.

Gradually, the galvanizing power of early Soviet poetry started to wane – until, at some point, creative writing became one of the major tools of dissidents and protesters. This transition is often associated with the rise of ‘Russian rock.’ Its lyrics are much more noteworthy than its music – in many cases, they were written by professional poets and mostly reflected protest sentiment. The band Kino captured hearts and minds with its hit song ‘We want change! and the rock band Nautilus Pompilius mocked the idea of being ‘Chained by one chain’ in its own critique of the Soviet system.

This new song tradition, along with its rebellious nature, carried over from the Soviet Union to the Russian Federation.

Read more

Spoiled by high art, people soaked in postmodern literature and music inspired by Western culture. Examples of this can be found in the poems of self-exiled writer Viktor Shenderovich or the Citizen Poet project that mocked domestic life and politics from an opposition activist’s point of view. The same is true of the music, although ‘Russian rock’ ended up replaced by ‘Russian rap.’ In many ways, it occupied the same niche of critique and satire, and was characterized by a strong liberal bias. This state of affairs remained relatively unchanged for over 30 years – until the fighting broke out, this spring.

Change on the cultural front

I kissed his cold dead lips,

I put a ring on his stiff finger.

I thought, I won’t be long, my dear,

And the war in the meantime continued.

These lines are from a recently published poem called ‘Call Sign: Paganel’ by Anna Dolgaryova who dedicated it to her fiance, an artillery captain who died in combat in the Lugansk People’s Republic in 2015.

Anna spent many years living in Ukraine. She worked in Kiev, but Euromaidan pushed her out: first, she left the capital for Donbass, then moved to Russia. There, her writing got noticed.

Poetess Anna Petrovna Dolgareva. © Anna Dolgareva

Many of Anna’s poems are about the events of 2014 in Donbass known as the “Russian Spring,” and many of them are poems of choice at festivals both in Russia and former Ukrainian territories liberated by Russia.

As a poet, Dolgaryova explores both how a conflict affects love and relationships and the daily life of people in war zones, in particular the people of Donbass:

Read more

A war has come to the city.

Bombs fall on the city.

A water pipe burst in the city,

and the water spills, a long muddy stream,

mixing with human blood as it flows.

She also dedicates many of her poems to Russian soldiers and officers:

I see them crossing the Smorodina River,

The Donets River, the River Styx,

Fighting for my bygone Soviet homeland,

For freedom for you and me.

To a certain extent Anna’s writing is a revision of feminist poetry with a heavy emphasis on the themes of war and patriotism. Russia has seen quite a number of new authors of fiction and poetry working in this genre, although most of them are believed by critics to rely heavily on the Western literary tradition.

What makes Dolgaryova’s writing stand out is how seamlessly she manages to conflate feminist poetry and a genre that has traditionally been on the opposite side of the spectrum, i.e., war poetry.

Another poet writing about the military operation is Igor Karaulov. Unlike many others, he has been an acclaimed writer for quite a while and belongs to a different generation (Karaulov was born in 1966). Many of his works have received favorable reviews from liberal critics and literary celebrities.

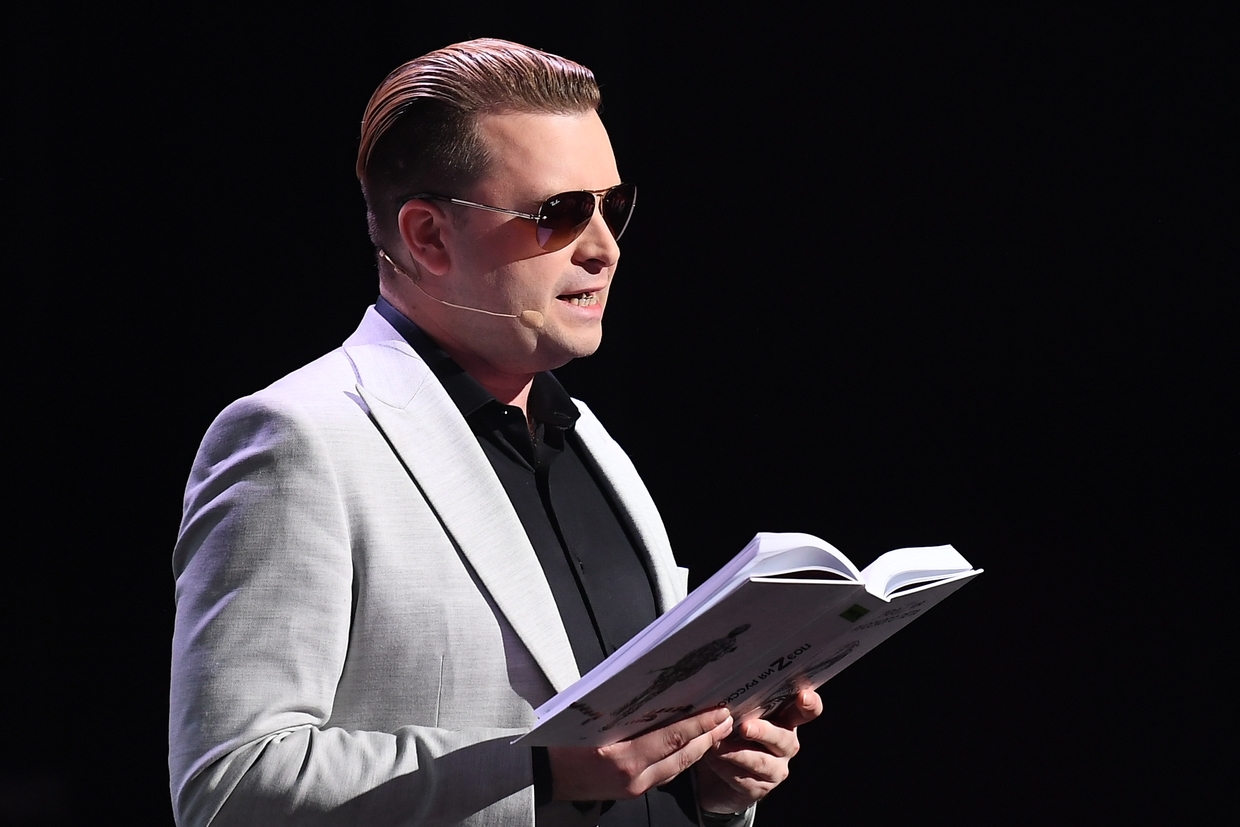

Poet Igor Karaulov at the ZOV poetry evening dedicated to the special operation in Ukraine at the Academy Concert Hall in Moscow. The event is organized by RT TV, which presents a collection of poems, ‘Poetry of the Russian summer’. © Sputnik/Ekaterina Chesnokova

Until February 24, 2022, Karaulov produced mainly post-modernist poetry rich in metaphors and abstract symbolism; however, after the launch of the military offensive he started to use his art to express his civic position on the ongoing events both at home and abroad. For example, he wrote a poignant epigram about the US House Speaker’s visit to Taiwan:

The world derailed as Pelosi deplaned.

There’s no leaving Taiwan in any manner.

Pray for our sins, oh Pope of Rome,

And hold on tight to your Vatican banner.

Alexander Pelevin (not to be confused with Russian popular fiction writer Victor Pelevin) also completed his evolution from postmodernism to patriotism in poetry. His novel ‘Pokrov-17’, which mixes prose and poetry, is also remarkable for mixing genres and realities and was recently awarded the Nation’s Literary Bestseller prize.

Following the start of the special military operation, Alexander Pelevin’s poetry became even more popular with readers than his fiction. He didn’t fail to respond to the wave of voluntary emigration provoked by the conflict and presented an alternative to the position of people who chose to flee their homeland:

I’m sorry I won’t leave. I’m sorry I’m so bad.

I’d rather be terrible and dark in my terrible and dark land.

Writer Alexander Pelevin at the ZOV poetry evening dedicated to the special operation in Ukraine at the Academy Concert Hall in Moscow. The event is organized by RT TV, which presents a collection of poems, ‘Poetry of the Russian summer’. © Sputnik/Ekaterina Chesnokova

He also dedicates his poems to Russian soldiers:

Good people need poetry, but they need UAVs even more,

As well as meds, armor, sights, all-weather raincoats, binoculars, flashlights.

Maria Vatutina, an acclaimed poet, playwright, and journalist, is among those who not only monitor current affairs but also produce a timely response to them:

Read more

The world is changing faster than ever.

In the meantime, however,

True heroes are being taken out by the filth of the world

From behind the corner in a cowardly plot.

Rap, the music of the trenches

Many popular performers chose to leave the country in response to the military offensive, including top rappers Oxxxymiron, Noize Mc and Face.

There is, however, no united opposition formed by any artists, nor are there any powerful hits that might enjoy the same level of impact on society that Kino’s single ‘We want change!’ had back in the 1990s.

In the meantime, patriotic rap songs are on the rise. For example, rapper Rich recently released his new track ‘Dirty work’ dedicated to the soldiers who protect our homeland and ensure that people in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kazan and other cities and towns of Russia can live a peaceful life.

Four letters L on the shoulder (a reference to the swastika sign on some Ukrainian military insignia – RT)

The peace-mongers’ feet are getting colder,

Iskander missiles will fly, huge as a boulder,

Targets hit by the Grads will smolder.

Chorus:

These guys do your dirty work

There’s no rest for them, no single perk,

They are under fire, and the enemies lurk,

This planet feeds on blood descending into murk.

Akim Apachev is a new name on the poetry scene that immediately attracted much attention. He is a former Ukrainian citizen and a resident of Mariupol. He is also the author of the single ‘Summer and Crossbows’ about Russia’s military operation in Syria that went viral on TikTok. The lyrics mention Ilyushin planes and PMC Wagner, among other things. The track became very popular with teenagers; it was a song of choice in Moscow’s bars and clubs, even as far as they were from the war zone in Syria.

As the heavy fighting over his hometown ended, Apachev did something very brave and exciting. He recorded a track in collaboration with Darya Frey called ‘A Duck is Swimming’, which is a direct reference to a Ukrainian folk song. This piece is important as it celebrates the liberation of a Ukrainian city from the grasp of the Kiev regime and is performed in Ukrainian.

The chorus goes like this:

Read more

A duck is swimming, girls are dancing,

At Azovstal demons are buried,

In a steppe, a house is on fire,

Our Lady gives birth to the baby.

The Azovstal factory was the last line of defense for Ukrainian nationalist fighters. Members of the Ukrainian army’s Azov Battalion were hiding for a long time on the grounds of this plant before surrendering to the Russian army.

The following line is of special significance: “This is my home, my Crimea, my land, and I will also take my Ukrainian language with me.” The divide between the Russians and the Ukrainians that exists in the Western mindset is challenged here.

The Mariupol-born artist says in Ukrainian: “This are my home and my language; I don’t support the Kiev regime.” These are the first lines written by a Ukrainian artist who believes the special military operation is justified and is ready to fight alongside Russia for peace for all – a Ukrainian who has a right to his homeland, his culture, his vision of a future for his country and who is ready to give his life for it.

A well-known producer from Kiev and a Ukrainian national Yuri Bardash is worth a special mention. He stayed out of politics for quite a while until he recorded his track ‘Poziciya’ (the title refers to the author’s political position) last summer slamming the Ukrainian regime. His hometown of Alchevsk is now under the control of the Lugansk People’s Republic. In his song, Bardash declares:

Question: What has the East to do with Bandera?

This is not our hero, not our faith

We have Stakhanov and Alchevsky

Heroes of Labor, super experts.

And he continues to tell Boris Johnson and Joe Biden to “go to hell.” Bardash had to move to Moscow because of his political views and now his former Ukrainian fans wish him dead. The story of Yuri Bardash sets a unique precedent: he’s the first well-known Ukrainian figure who spoke up for Russia openly. He wasn’t afraid to say what many wouldn’t dare out of fear of persecution by the SBU (the Security Service of Ukraine).

***

On the whole, there are two things to be said about the output inspired by the military operation. First, it is taking over a niche previously occupied by other popular forms and genres and ranges from feminist poetry to salty epigrams. Another thing worth mentioning is that this kind of work is written both by the authors who stay true to the Russian literary tradition with a clear preference for epic narratives and those who re-invent the traditions originating in the West, such as feminist poetry or free verse.

It is likely that all this is just the beginning.

By Sergey Izotov, Moscow-based journalist and Russian poet