Who was the country’s greatest social and political philosopher of the 20th century, and what were his main ideas?

© RT / RT

Among the many great Russian writers of the 20th century, one man stands out in particular, whose works have had the greatest impact on social and political views on modern life in the country. This Nobel Prize winning philosopher is often quoted by Russian President Vladimir Putin. An ideologist who had envisioned the turn from Soviet ideology (which ran the show for 70 years) to the period of national revival, he also predicted the conflict in Ukraine half a century before it occurred.

This man is none other than the great writer and philosopher Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. On February 12 –the 50th anniversary of his arrest and subsequent expulsion from the Soviet Union – RT recalls the life of Russia’s national philosopher.

The philosopher’s youth

“His heart, soul and thought were filled with pain for the Fatherland and unfailing love for it. These feelings were a driving force of his creative endeavor. He clearly distinguished authentic, real, people’s Russia from the totalitarian system that plunged millions of people into sufferings and hard trials,” said Russian President Vladimir Putin at the unveiling of the monument to Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 2018.

In just a few words, the President succinctly summed up his attitude to one of Russia’s outstanding social and political thinkers of the 20th century, whose intellectual heritage influences Russian politics to this day.

Read more

Solzhenitsyn was born in December 1918, in the tragic years of the Russian Civil War. His parents were peasants from the south, who, through hard work and perseverance had managed to earn a good living before the conflict.

During the Civil War, his family’s home was destroyed. The future writer spent his childhood in Rostov-on-Don. The family was poor and Solzhenitsyn was often teased by his classmates for wearing a cross and refusing to join the pioneer movement. Despite this, Solzhenitsyn studied well, graduated from school with honors and was admitted to the Physics and Mathematics Department of the Rostov University.

Though excelling in his studies, even becoming a Stalin prize laureate, literature soon became Solzhenitsyn’s main pursuit. By that time, he was already writing short stories, poems, and essays. However this particular period was short-lived. With the start of WWII, the writer’s life changed overnight – and so did the whole country’s.

From the front line to labor camps

Due to health problems, Solzhenitsyn was not immediately drafted into the army. However, in the fall of 1941, he was accepted into the armed forces. He studied at an artillery academy and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. Solzhenitsyn was engaged in so-called “sound reconnaissance” – with the help of special equipment, he identified the location of the enemy’s artillery and helped the Soviet army destroy it.

A combat hero with multiple decorations, Solzhenitsyn marched from Orel all the way to East Prussia alongside the Red Army. However, in February 1945, three months before victory, he was suddenly arrested by the Soviet counterintelligence organization SMERSH.

The reason for the arrest was quite banal – the writer had made critical remarks about Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. In his diaries and letters addressed to friends, Solzhenitsyn called Stalin a “pakhan” (i.e. leader of a criminal gang, in Russian criminal jargon), accused him of distorting “Leninism”, and compared Stalin’s regime with serfdom.

After being interrogated in Lubyanka prison for three months, Solzhenitsyn was found guilty of counterrevolutionary activities and sentenced to eight years in labor camps. Some fortune smiled upon him however, and he spent the first five years of his term working in so-called “sharashkas” – closed institutions that developed advanced technology for military purposes – where mathematicians, engineers, and other key specialists worked.

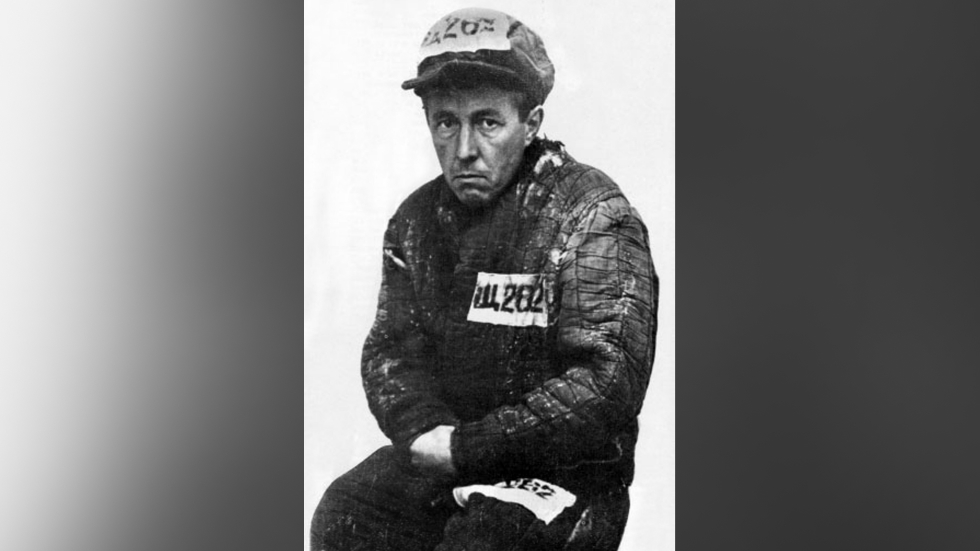

However, in 1950, after a conflict with the management of the camp, Solzhenitsyn was sent to the infamous Gulag – a hard labor camp in Ekibastuz, in the eastern steppes of Kazakhstan. The horrible conditions of Stalin’s camps made a great impression on Solzhenitsyn, and these memories became the basis for one of his most significant literary works — the story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich”.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn the day of his liberation in 1953 after 8 years in Gulag. © Apic/Getty Images

From renown to exile

In 1953, Solzhenitsyn was released from the labor camp, but his punishment did not end at that. In this new period of his life, the writer was exiled to a Kazakh village. Also at this time, he was diagnosed with cancer and received treatment in Central Asia. He recovered and was able to return to Russia only in 1956. A year later, the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court fully rehabilitated the writer, stating that his actions did not constitute a crime.

The years he spent in labor camps and exile led Solzhenitsyn to become disillusioned with communist ideology, and he developed an interest in national-conservative and Christian Orthodox values. The USSR was undergoing the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw” – a period when social and political repressions were relaxed and many authors who were previously censored by the Soviet government were given more freedom to work. Solzhenitsyn too fell under this category.

While working as a physics and astronomy teacher in a school in Ryazan – a regional center with a population of 250,000 people – Solzhenitsyn also wrote intensively. His story “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” was praised by prominent Soviet authors such as Konstantin Simonov, Alexander Tvardovsky, and Korney Chukovsky. In 1962, Khrushchev personally ordered the story to be published. Soon, it was translated into other languages, and Solzhenitsyn was accepted into the USSR Union of Writers.

The story was praised not only by Soviet leaders and famous writers. Solzhenitsyn started to receive countless letters from former prisoners of the Stalin camps who thanked him and shared their personal experiences. These letters eventually served as the basis for his famous novel on the subject of repressions, “The Gulag Archipelago”. In parallel, Solzhenitsyn traveled to Tambov region, where he collected information about an anti-Soviet peasant uprising during the Civil War. The collected materials formed the basis for his cycle of novels “The Red Wheel”.

When Leonid Brezhnev became General Secretary of the Communist Party, his predecessor Khrushchev’s liberal initiatives were quickly curtailed. The KGB seized Solzhenitsyn’s archives and he was expelled from the Union of Writers. Nevertheless, his works were distributed as “samizdat” [in Soviet times, self-published copies of censored and underground literature] and published abroad. In 1970, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize “For the moral force with which he followed the immutable traditions of Russian literature”. However, the Soviet leadership saw in him a stubborn ideological enemy.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn receives the Nobel Prize for Literature awarded by King Karl Gustav of Sweden. © James Andanson/Sygma via Getty Images

A few months before he was deported from the USSR, Solzhenitsyn wrote an open “Letter to the Leaders of the Soviet Union”, addressed to the Central Committee of the CPSU. He accused Soviet leaders of being “nationless”, and called on them to take a firm national stance and “feel the entire 1100-year [Russian] history behind their backs, and not just [the past] 55 years, or 5% of it.”

Solzhenitsyn called on the USSR’s leadership to let go of communist ideology and stop supporting leftist regimes across the world, which prevented development within the country: “We should not be governed by considerations of political gigantism, nor concern ourselves with the fate of other hemispheres. … Our country should be guided by considerations of the inner, moral, healthy development of its people. We should liberate women from the forced labor of earning money – especially from the crowbar and the shovel; improve schooling and children’s upbringing; preserve soil, bodies of water, the whole of Russian nature, and restore healthy [living in] cities.”

In his letter, Solzhenitsyn also talked about the need to introduce democratic social principles, stop ideological oppression and religious persecution, develop private initiative and actively support the economy. In general, in this farewell message to the Soviet leadership, the writer proposed a plan for the reconstruction of the country and rejected the ideological foundations of communism.

Soviet leaders undoubtedly read it – Solzhenitsyn was a prominent intellectual and public figure who could not be ignored – and promptly expelled him from the country.

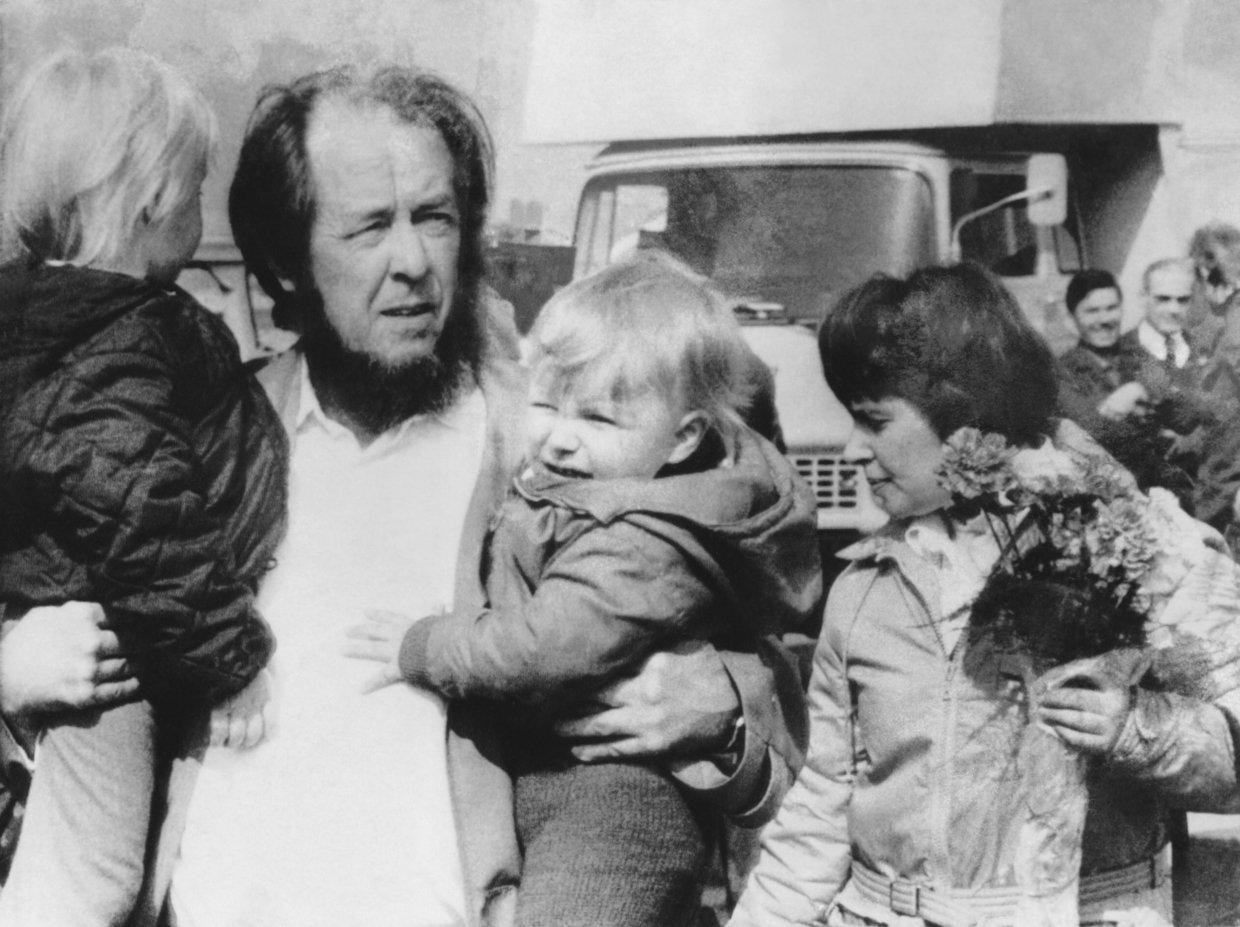

On February 12, 1974, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and accused of high treason and “systematically committing acts incompatible with possessing USSR citizenship”. The next day, he was deported from the Soviet Union.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn with his family as he arrives at the Zurich airport from Moscow, Zurich, Switzerland, March 29, 1974. © Underwood Archives/Getty Images

To the West and back

Solzhenitsyn wandered around several Western countries for a couple of years, until he eventually settled in the US state of Vermont in 1976. This remote place on the border with Canada was ideal for the philosopher’s reclusive life. However, it’s not true that in the US, Solzhenitsyn merely lived in the countryside and wrote for his own pleasure.

Having talked to many Western politicians and ideologues, he soon realized that no one was going to save Russia from the totalitarian communist regime. However, there were plenty of people who wanted to “finish Russia off” – US politicians who called Russians “occupiers”, military authorities who were discussing nuclear strikes, and emigrants who feared Russia’s national revival.

“The teeth of the Russophiles are already tearing Russia’s name to pieces. So what will happen later, when, weak and feeble, we will climb out from under the ruins of the diabolical Bolshevik empire? They won’t even allow us to get up,” Solzhenitsyn wrote in his memoirs, “Between Two Millstones”. In the West, he sought to defend Russia’s history and its future, seeing both the Soviet government and the imperial ambitions of the US as a threat to Russia.

Preserving national independence and defending the interests of Russia and its people become key themes in Solzhenitsyn’s creative work.

During the perestroika years, official attitudes towards Solzhenitsyn began to change. He was rehabilitated and his citizenship was restored. In 1994, Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia. He flew from the US to Magadan and then traveled across Russia by train, becoming, in his latter years, a real hero to Russians.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn arriving in Magadan, Russia, after he had spent 20 years abroad. © Sputnik/D. Korotaev

Solzhenitsyn died in Moscow in 2008, at the age of 89. His funeral was attended by Vladimir Putin, who was then prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev, the President of Russia, as well as the President of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the rector of Moscow University, many officials, and thousands of ordinary people who came to pay their last respects.

Rebuilding Russia and the world

Solzhenitsyn’s social and political views are expressed in many of his books, short stories and articles. But the title of one, “Rebuilding Russia”, perhaps best expresses Solzhenitsyn’s entire philosophy in this regard.

Solzhenitsyn’s desire to “rebuild” Russia cannot be reduced to a particular ideology. In general, he was a staunch supporter of traditional values, noted the importance of the family, and encouraged population growth. As a former prisoner of the Stalin camps, he opposed repressions and oppression. He supported the development of the country, private initiative and a free national economy. His views were based on the 1,000-year history of Russian statehood and the historical strength of the Russian people.

Solzhenitsyn also regularly spoke about the West and its attitude towards Russia. Having lived in Western Europe and the US after being expelled from the USSR, he discovered that Russia would not find friends there, but only cynically-minded imperialists blinded by their sense of superiority. “But the persisting blindness of superiority continues to hold the belief that all the vast regions of our planet should develop and mature to the level of contemporary Western systems, the best in theory and the most attractive in practice … Countries are judged on the merit of their progress in that direction. But in fact such a conception is a fruit of Western incomprehension of the essence of other worlds, a result of mistakenly measuring them all with a Western yardstick.”

Speaking at the Valdai Forum in 2022, President Putin quoted Solzhenitsyn’s words about the West being “blinded” by neocolonialism and unipolarity.

Solzhenitsyn’s criticism of the West’s foreign policy only grew stronger over time. In 2006, two years before his death, he accused the US of occupying several countries. “This has been the case in Bosnia for nine years, in Kosovo and Afghanistan for five years, and in Iraq for three years so far, but the situation there is sure to last a long time.” He also noted that Russia does not pose any threat to the US which continues to expand its military presence in Eastern Europe and encircle the country from the South.

However, he was concerned not just with foreign policy, but also with the negative changes in Western society. “You have preserved the term, but replaced it with another concept: a small [idea of] freedom, which is merely a caricature of freedom in the larger sense; freedom without responsibility or a sense of duty,” Solzhenitsyn said in an interview with French journalists in 1975.

After the collapse of the USSR, he noted that during the Cold War, people got used to “having an enemy”. “And presently, some may feel confused. But ancient wisdom tells us that man is his own worst enemy, and [likewise], society is its own worst enemy… Christianity teaches us to first of all fight the evil within ourselves.”

For Solzhenitsyn, the question of moral development was virtually inseparable from social and political issues. His frequent appeal to the sense of duty and personal responsibility refers to eternal values that are incredibly rare among the Western thinkers and leaders of our time.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Russian President Vladimir Putin [foreground, left to right] and Solzhenitsyn’s sons Stepan and Yermolai [back row, left to right] meet at Solzhenitsyn’s house in Troitse-Lykovo. © Sputnik/Mikhail Klimentyev

The Ukraine issue

Was Solzhenitsyn a prophetic visionary or just extremely sensitive to what was happening in the world? Probably the latter. 23 years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Soviet propaganda was still permeated with ideas of brotherhood and the friendship of peoples, Solzhenitsyn wrote about the forthcoming problems with Ukraine.

“With Ukraine, things will get extremely painful” – these words from the fifth part of “The Gulag Archipelago”, written by Solzhenitsyn back in 1968.

In the article “Rebuilding Russia”, Solzhenitsyn advocated the unity of the Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian peoples. He accused the old Austrian Empire of essentially creating a separate, anti-Russian Ukrainian nation.

Read more

“To cut Ukraine off from a living organism (including those regions which had never been part of traditional Ukraine: the “Wild Fields steppe” of the nomads – what later became Novorossiya, as well as Crimea, Donbass, and lands stretching almost to the Caspian Sea) … To separate Ukraine today would mean to cut across the lives of millions of individuals and families: the two populations are thoroughly intermingled; there are entire regions where Russians predominate… Together we have borne the suffering of the Soviet period, together we have tumbled into this pit, and together, too, we shall find our way out,” Solzhenitsyn wrote.

Later, he touched upon the problems in Ukraine that were relevant in 1991: “In various places, people are already complaining about mass violence and being fired from work because of their nationality; soon, minorities may be deprived of the right to educate their children in their native language, as the Communists had done earlier. Our common bitter Soviet experience has sufficiently convinced us that violence cannot be justified by any state ideology.”

Incidentally, already in those times, the writer noted who stood behind the events in Ukraine. “The US wholly supports every anti-Russian initiative in Ukraine. What the US wants is for Ukraine to turn against Russia. One cannot help but recall the ‘immortal’ project pushed forward by Parvus in 1915: to use Ukrainian separatism in order to bring about the collapse of Russia.”

Ukraine’s anti-Russian political course and the serious risks posed by Ukrainian radicals prompted Solzhenitsyn to express the following ‘formula’ in regard to Russia’s historical lands: “I love [Ukrainian] culture and genuinely wish all kinds of success for Ukraine – but only within her real ethnic boundaries, without grabbing Russian provinces.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin at the ceremony marking the unveiling of a monument to writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn on December 11, 2018. in Moscow, Russia. © Sputnik/Sergey Guneev

Communist myths

Solzhenitsyn’s intellectual legacy is incredibly valuable for modern Russia. President Putin has repeatedly called him “a true patriot of Russia, a nationalist in the good, civilized sense of the word”. He also noted that the writer did not allow anyone to speak disparagingly about Russia and opposed any signs of Russophobia.

However, Solzhenitsyn’s social and political views have not received unconditional support in Russia. His harsh criticism of the Soviet Union still provokes the anger of leftist groups, and to this day, communists view him in a highly negative light. Incidentally, communists often criticize Solzhenitsyn for the myths which had been invented by their own party.

For example, the biggest myth about Solzhenitsyn pushed forward by the communists is the belief that in his infamous 1978 speech at Harvard, the writer called on the US to carry out a nuclear attack on the USSR. This is a rather persistent myth, which even State Duma deputies from the Communist Party occasionally refer to.

In reality, Solzhenitsyn never mentioned anything like that either in his Harvard speech, or anywhere else. As Viktor Moskvin, Director of the Solzhenitsyn House of Russia Abroad, explained in an open letter to Communist Party deputy Leonid Kalashnikov, the myth that “Solzhenitsyn called for the nuclear bombing of the USSR” arose from his novel “The Gulag Archipelago”, an excerpt of which was distorted by communist propaganda. However, the myth is highly convenient for communists, so it persists.

Solzhenitsyn is also criticized from time to time by representatives of Russia’s ruling party. For example, in 2023, the First Deputy Head of the United Russia faction Dmitry Vyatkin called for the exclusion of Solzhenitsyn’s works from the school curriculum, because he believed that they “did not pass the test of time” and the writer had allegedly “smeared his own homeland with mud”.

Read more

The proposal was not backed by the authorities and Solzhenitsyn’s work continues to hold a prominent place in Russian literature textbooks.

A prophet in his Homeland

Solzhenitsyn himself was never particularly concerned about the opinion of critics. The fact that modern Russian politics have been greatly influenced by his philosophy is, in itself, the greatest recognition of the writer’s work.

Russia has reclaimed historical lands – such as Crimea and parts of Novorossiya– that were given away by the Bolsheviks; the government strictly suppresses any attempts at separatism; the authorities implement measures aimed at population growth and focus on developing, rebuilding, and improving the country; and by comparison to Western countries, Russia has made attempts to become a stronghold of Christian conservatism and traditional values.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was not an idealist – as a combat officer, war hero, and survivor of Stalinist camps, he may hardly be called such. Solzhenitsyn’s reasoning was always sober and pragmatic, he had a perfect understanding of Russia and its people. Russia owes a lot to Solzhenitsyn, and the direction in which the country is moving today is largely attributable to him.

By Maxim Semenov, a Russian journalist focusing on the Post-Soviet states