The Soviet Union’s key filmmaker of the post-war era laid the foundation for the kind of output taken for granted by movie lovers today

© RT

In the history of world cinema, the Soviet Union had two standout periods – the 1920s, during the boom of avant-garde cinema, and the late 1950s and early 1960s, during the “Khrushchev Thaw” (which was named for the opening up of society under the eponymous Nikita, after the years of terror under Joseph Stalin).

While the legendary Sergei Eisenstein, and other giants of the pre-war period, developed techniques that influenced the filming and montage of modern blockbusters, pictures of the latter period inspired arthouse genres.

Among the many post-war Soviet film directors, Andrey Tarkovsky had the greatest impact on world cinema. In 2018, the term “tarkovskian” – describing his unique “slow” and meditative style – was added to the Oxford Dictionary. Since Tarkovsky’s death in 1986, the influence of his cinematic style has spread from international film festivals to rock music clips and even video games.

Read more

Tarkovsky has a complicated reputation. His movies are often called “slow” and “boring.” However, he remains the only Russian filmmaker of the second half of the 20th century whose work has become a yardstick for representatives of arthouse cinema, and whose name has inspired a search for a successor – for example, Mexican filmmaker Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and the Russian Andrey Zvyagintsev have both been called the “new Tarkovsky.”

What is it that makes Tarkovsky and his work so unique?

War, home, and first films

He was born in 1932. His father was poet Arseny Tarkovsky and his mother Maria – who later became the main character of one of his most prominent films, ‘The Mirror’ – was descended from the Dubasov noble family. She also attempted to write, but didn’t manage to build a literary career. Citing a “lack of talent,” she destroyed all her manuscripts.

Although Tarkovsky spent most of his life in Moscow, he was born in the village of Yuryevets in the Ivanovo region (about 500km northeast of the capital). After World War Two broke out, he was evacuated there with his mother – by that time his father had left the family. They lived in the village for just two years, but the wooden house would later reappear in ‘The Mirror’ as a symbol of an idyllic childhood. Throughout his life, Tarkovsky was haunted by the utopian image of “home.” In his films, a happy domestic life exists only in dreams (e.g., the central character’s “lost” younger years from ‘Ivan’s Childhood’) and memories. Meanwhile, Tarkovsky’s adult heroes often leave home (‘Solaris’), search for it (‘Nostalgia’), or destroy it (‘Sacrifice’).

Andrei Tarkovsky © Sputnik / Alexander Makarov

In 1954, Tarkovsky entered the VGIK – the USSR’s most famous film institute. The beginning of his studies coincided with the Thaw period of cinema, which was radically different from previous Soviet movie eras. Young filmmakers who had gone through the war, or encountered it as children, were at the center of this new wave. During the Khrushchev years, the traditions of Stalin-era war cinema were reimagined. Similar processes occurred in other countries that contributed to the victory in WWII. The new motion pictures focused not on soldiers and battles, but on the unseen victims of the war for whom there was no place in Stalin’s movies.

Read more

In the same year as Tarkovsky was admitted to VGIK, French critic and future film director Francois Truffaut published an article titled ‘A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,’ where he formulated the Auteur Theory. Truffaut described how the filming process in earlier times was managed by producers and screenwriters, but how the director had become the key figure on the set, determining what to shoot and, most importantly, how the footage would be edited. The ‘auteur’ could be a director with an individual style or, as Tarkovsky said, an artist whose personality is “so significant that it determines the artistic qualities of the work.” Yet Tarkovsky was even more radical in his views on the nature of cinema than the French critics. He insisted that ‘auteur’ is a “qualitative concept” stating that, “good cinema is ‘cinema d’auteur.’ A good director is one who has a strong individuality and particular views on the phenomena of life.”

All that remains from Tarkovsky’s student period are several short films and his diploma work ‘The Steamroller and the Violin,’ which is thematically and stylistically close to Thaw cinema. It tells a story of friendship between a child violinist and a steamroller machine driver. Compared to the director’s mature works, this traditional and realistic featurette is often relegated to the background. However, this ‘student’ film first shows us the artist-protagonist who is to become the focal point of Tarkovsky’s work. His semi-autobiographical characters that grow up alongside their author – from the little musician of this debut work to the elderly writer from his final film, ‘The Sacrifice’ – invariably face the unknown, whether it is a socially-distant driver of a steamroller, the wish-granting room of ‘Stalker,’ or the divine revelation of his last movie.

Tarkovsky did not consider ‘The Steamroller and the Violin’ a great success and did not like talking about it. However, the film did its job – the director graduated from the institute with honors.

‘The Steamroller and the Violin’ (1960) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

Global recognition and first conflicts with the authorities

Tarkovsky’s first full-length picture was the war drama ‘Ivan’s Childhood.’ Initially, this film – based on the story ‘Ivan’ by Vladimir Bogomolov – was shot by another director. However, Mosfilm Studio found that version “unsatisfactory.” It was particularly criticized for the free treatment of the original text in which the young partisan, Ivan, who was killed at the end of the story, instead survived in the movie and went on to volunteer in the Virgin Lands campaign. This new ending wasn’t approved by Bogomolov and completely contradicted his idea. The writer recalled how he contacted the newspaper which published an article about child partisans with an appeal, “Young heroes, respond!” As Bogomolov found out, no one responded – because no one had survived.

Read more

Tarkovsky was given limited time and the remaining budget to shoot his version. He significantly reworked the original text, focusing on the inner world of the child partisan Ivan. Dreams became key to his story. In these dreams, the boy sees his lost mother and lives a happy childhood. In ‘Ivan’s Childhood,’ the ‘real world’ doesn’t hold back the dark, repressed desires of the subconscious. On the contrary, this real world is dark and cruel. As film critic Oleg Kovalov writes, the paradox of war is that “the poor child’s striving towards harmony, light, peace, and kindness become an almost shameful desire, a secret perversion.”

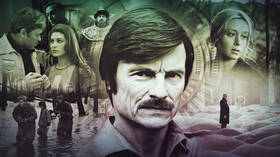

‘Ivan’s Childhood’ won Tarkovsky the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and brought him worldwide fame. At that time, ‘Thaw cinema’ was popular abroad and often received prizes at international festivals. In 1958, M. Kalatozov’s war melodrama ‘The Cranes are Flying’ won the Palme d’Or in Cannes, and in 1961, G. Chukhray’s film ‘Ballad of a Soldier’ won the BAFTA Award. Like ‘Ivan’s Childhood,’ these movies looked at the war in a new way, moving away from heroic narratives and turning to the stories of its victims.

Tarkovsky’s next movie was a medieval drama about the great painter of icons – Andrey Rublev. Despite a deep immersion in the medieval era, the director wasn’t obsessed with accurately reflecting the realities of the 15th century. In Tarkovsky’s movie, Rublev, whose biography is practically unknown, is shown as an artist working in the horrible conditions of internecine wars, famine, and surrounding violence. His Rublev is a far cry from the ‘artist inspired by the people’ – the image approved by party officials. Tarkovsky has Rublev go through a loss of faith in people so that he may regain it in the finale after meeting the young bell caster Boriska. In an interview unpublished during his lifetime, Tarkovsky says that “the artist is the conscience of society” and the person who’s most sensitive to changes.

‘Ivan’s Childhood’ (1962); ‘Andrei Rublev’ (1966) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

During the production of ‘Andrey Rublev,’ a conflict first emerged between Tarkovsky and the Soviet officials who oversaw the studios. The movie was constantly edited, the major scene depicting the Kulikovo Battle didn’t get the required funding (after the film’s release, the press criticized the director for cutting this scene during final edits), and Tarkovsky was accused of excess violence. Eventually, the work was cut by 30 minutes and allowed only limited release three years after it was completed.

Read more

Aesthetic dissident

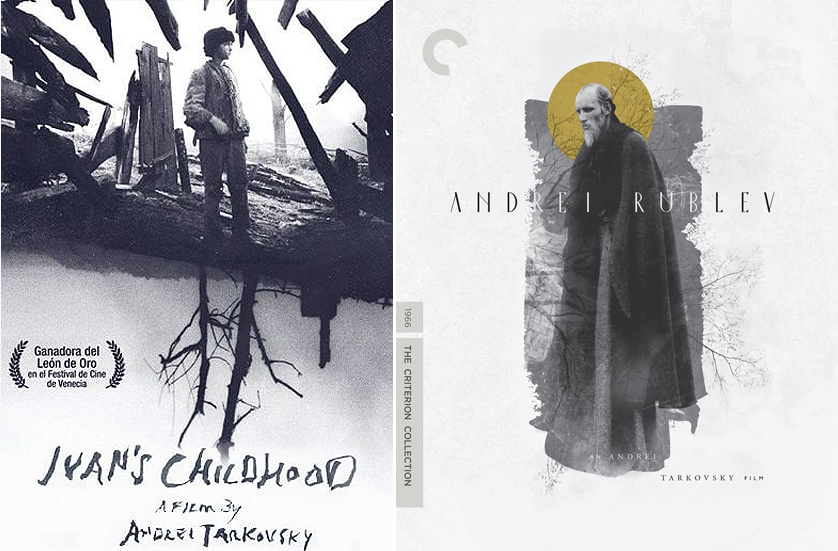

After two movies focusing on past experiences, the events in Tarkovsky’s next picture unfolded on a space station in the near future. Despite the science fiction genre, ‘Solaris’ – a free adaptation of the novel by Stanislaw Lem (the author wasn’t satisfied with the film and said that Tarkovsky shot ‘Crime and Punishment,’ not ‘Solaris’) – is based on familiar themes: the conflict between reality and fantasy, human memory, and loss of home.

Tarkovsky didn’t like genre films and entertainment movies, but science fiction provided a greater sense of allegory than historical events. While filming ‘Solaris’ and ‘Stalker,’ he could explore ideas that interested him while also feeling less pressure from the Communist Party. In her book on Tarkovsky, film critic Maya Turovskaya wrote that Tarkovsky was not a political, but an “aesthetic” dissident, and having minimal outside interference in his work was more important for him than political and economic freedom.

In his next movie, Tarkovsky wanted to explore the phenomenon of memory and to set himself free from the conventions of any genre. Initially, ‘The Mirror’ was planned as an interview film in which the filmmaker’s mother was asked a variety of questions – ranging from her own life to the Vietnam War – while being filmed with a hidden camera. Tarkovsky soon abandoned this idea and made a feature film, but one that was unique in its form.

‘Solaris’ (1972); ‘Mirror’ (1975) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

Tarkovsky’s co-author, screenwriter Alexander Misharin, remembered the first screening of ‘The Mirror’ by the chairman of the USSR State Committee for Cinematography who remarked, “Surely, we have freedom of creativity. But not to such an extent!” ‘The Mirror’ was in many ways the opposite of the director’s previous film. The action descended from space to earth, and instead of a clear plot, it was based on a fragmented narrative imitating human memory where characters and events are layered on top of each other. For example, the main character’s mother and wife are played by one actress, which confuses the viewer and blurs the lines between childhood and recent events.

Read more

Instead of a simple, almost non-existent plot, the film is based on visual and thematic ‘rhymes’, which is why ‘The Mirror’ is often called “poetic cinema.” The film is based around the memories of a dying man in whose mind wartime childhood memories blend into the landscapes of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, historical chronicles rhyme with personal experiences, and his mother’s memories intertwine with his own.

By the decision of the State Committee for Cinematography, the film was not widely distributed in the USSR, although it was sent to Cannes. The film’s “unfriendly” exploration of consciousness and memory sealed Tarkovsky’s status as an ”aesthetic dissident.”

The director’s last movie in the USSR was ‘Stalker’ – a fantastic parable about the journey of the three main characters to a place where secret wishes are fulfilled. The filming process was accompanied by a series of misfortunes: the script was rewritten over ten times, the movie had to be reshot due to a technical issue in which several thousand meters of film were improperly developed and ruined, and Tarkovsky suffered his first heart attack. Stalker acquired the reputation of being a ‘cursed movie’ when, following the premiere, several members of the crew died within a short time, including the director’s friend and one of his regular actors, Anatoly Solonitsyn, who played the role of the Writer.

‘Stalker’ (1979) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Mosfilm

After the futuristic ‘Solaris’ and the experimental ‘Mirror,’ ‘Stalker’ seems almost ascetic. Tarkovsky’s late works increasingly gravitate towards compositional simplicity and limited space – “finding a reflection of infinity in a small space.” For example, the characters in ‘Stalker’ don’t have real names, only nicknames (Stalker, Writer, Professor), and the picture’s post-apocalyptic world is much closer to the stagnant Soviet Union than the ‘city of the future’ from ‘Solaris.’

Read more

Conflict with the authorities

Tarkovsky shot only seven full-length films in his 25 years of filmmaking, but up to the very end of his life, he had many creative plans. One of these was to work on a film in Italy – and in fact, this turned into the movie ‘Nostalgia.’ Tarkovsky waited for permission to start filming for over three years. He finally obtained it with the help of Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra, who had some influence over Soviet officials. With Guerra, Tarkovsky began writing the script about a man traveling through Italy.

In 1980, Tarkovsky went to Italy to prepare for filming. While there, he had the chance to compare two styles of filmmaking – Soviet and Western. Tarkovsky didn’t have a preference for either and pointed out the shortcomings of each. While capitalist society gave the artist full freedom of expression, it also provided fewer opportunities for making his idea come to fruition.

In many ways, ‘Nostalgia’ anticipated Tarkovsky’s own future fate. The main character is a Russian writer who, like the protagonists of his previous films, travels not so much through Italy as through the realms of his own memory. Tarkovsky reveals the inner experience of emigration where the protagonist is stuck between two worlds, fully belonging to neither of them.

Tarkovsky did not initially plan on permanently leaving the USSR. Despite the fact that he and his wife were allowed to go to Italy, his son and mother had to stay in the USSR. Andrey Tarkovsky Jr. later said that they were left as “hostages” in the Soviet Union to prevent his father from permanently emigrating to the West. What exactly happened remains unknown, but apparently the leadership of the State Committee for Cinematography decided that Tarkovsky had become a so-called “non-returnee” and that he did not plan on coming back to the USSR. His name was banned from print in the USSR, and the Soviets withdrew from the production of ‘Nostalgia.’

‘Nostalgia’ (1983) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky © Sovinfilm

Tarkovsky’s letters to the general secretaries of the CPSU Central Committee Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, in which he asks to work and live in Italy with his family for three years, have been preserved. The filmmaker emphasized that his last picture, ‘Nostalgia,’ was about “homesickness experienced by a Soviet person temporarily finding himself abroad” and that he had no plans to emigrate.

Read more

While Tarkovsky worked in the USSR, his relations with censors got progressively worse. At the premiere of ‘Nostalgia’ at the Cannes Film Festival, the Soviets, represented by film director Sergei Bondarchuk, went to great lengths to make sure that Tarkovsky would not receive the main prize. The confrontation ended in an open conflict. In a letter addressed to Secretary General Chernenko, Tarkovsky stated 11 points that demonstrated unfair censorship of his work. Among these were: illegal restrictions on the public release of his films, boycotts by USSR awards committees and film festivals, no press coverage, and the sabotage of ‘Nostalgia’ in Cannes. The betrayal he experienced in Cannes and in his homeland convinced Tarkovsky not to return home. In the summer of 1984, Tarkovsky announced his decision to stay in the West.

Farewell

‘The Sacrifice’ became Tarkovsky’s last movie, most of which was filmed in Swedish. Tarkovsky was invited by the Swedish Film Institute, which covered most of the film’s expenses. He was a big fan of the great Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, who lent the Russian director part of his own film crew: Bergman actor Erland Josephson played the leading role, cinematographer Sven Nykvist, who worked with Bergman on all his main films, was the cameraman, and the filmmaker’s son, Daniel Bergman, was his assistant. Moreover, Josephson and Nykvist invested some of their own funds into the film, becoming its co-producers.

By the time filming was over, Tarkovsky was diagnosed with lung cancer. ‘The Sacrifice’ – the story of an aging man who sacrifices his regular life and burns down his house to prevent a nuclear war – is often called ”prophetic.” It stands as both the final testament of the dying filmmaker and a prophecy of the Chernobyl disaster that occurred just a few weeks before the premiere.

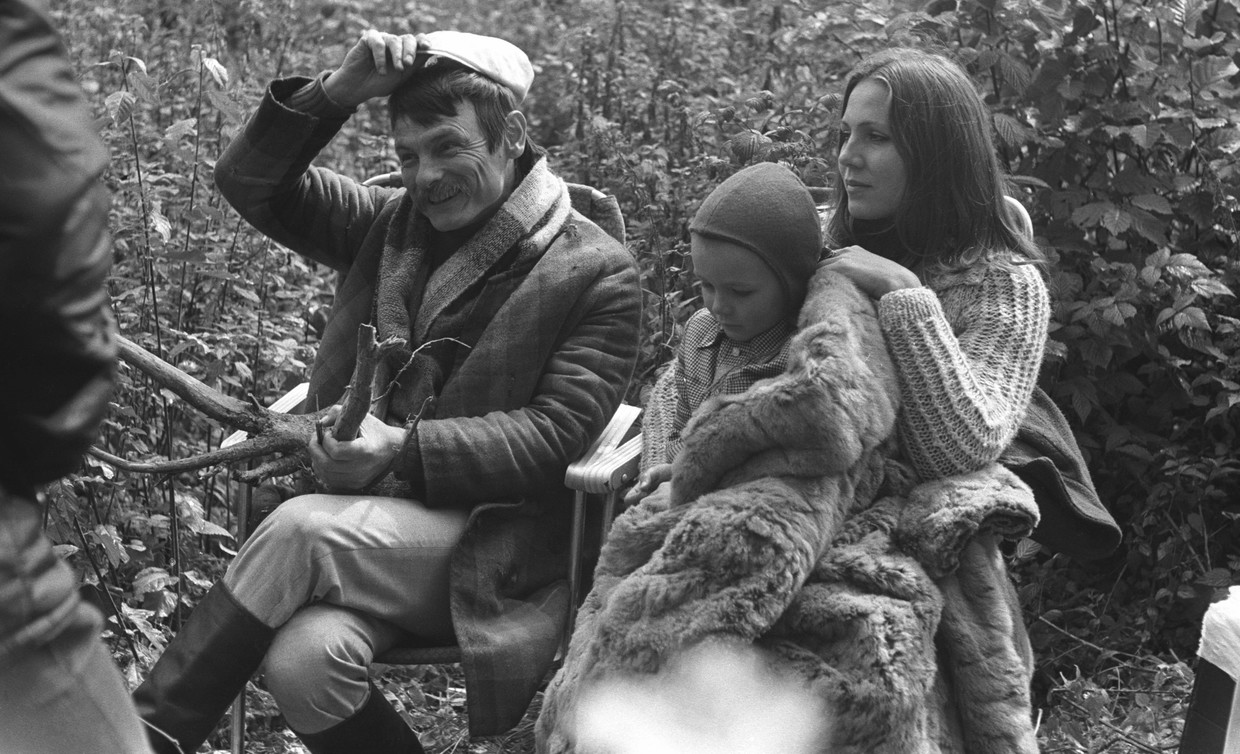

Film director Andrei Tarkovsky on the set of the movie ‘Stalker’ in 1977. In the picture: Andrei Tarkovsky and Larisa Tarkovskaya. © Global Look Press / Igor Gnevashev / Russian Look

Five years after Tarkovsky’s departure from the USSR, his sixteen-year-old son was allowed to visit his sick father. According to Alexander Gordon, a friend and co-author of Tarkovsky’s early works, party officials knew about Tarkovsky’s diagnosis, but for a long time did not disclose it to his family. At that time, Tarkovsky’s previously banned movies were once again released in the Soviet Union.

Tarkovsky died at the end of 1986, at the age of 55. A few days later, the USSR State Committee for Cinematography released an obituary, expressing “bitterness and regret” that the filmmaker had worked away from his homeland in his final years.

Tarkovsky was buried at the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery near Paris – the final resting place of many Russian émigrés, writers of the Silver Age, and members of the White Movement.

By Timofey Konstantinov, Moscow-based journalist