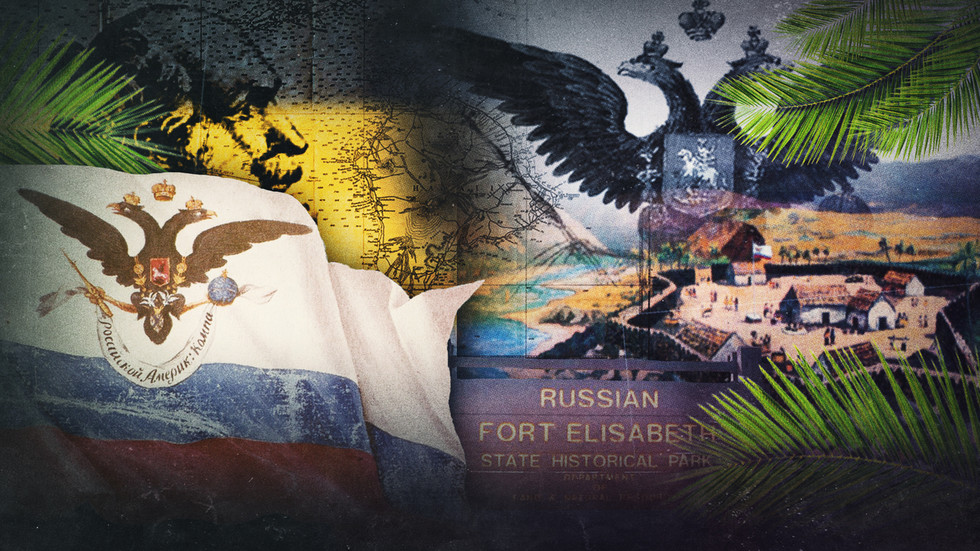

Failure to secure the islands shows why Saint Petersburg couldn’t gain a foothold in the New World

© RT

Almost everyone in Russia and the United States is familiar with the story of how Alaska was sold to the Americans for next to nothing. Considerably fewer people have heard about the Russian colony in California. And only historians seem to know that mere chance prevented the future 50th state of the US from becoming a part of the Russian Empire 205 years ago.

Read more

The “Schaffer scam,” as those events are known in American historiography, was a fleeting episode of the colonial era. But that doesn’t make the story any less exciting.

What truly happened on the Sandwich Islands between 1815 and 1817, why did a Bavarian doctor christen native chiefs in memory of Russian heroes of the Napoleonic War, and when were the last human sacrifices in Hawaii?

The ‘soft-shell crab’ as a great conqueror

The first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii had a difficult childhood. He was born in the middle of the 18th century to a noble family on the archipelago’s largest island. The clans of the tribe were constantly at war with each other and with neighboring tribes – for centuries there raged a classic “war of all against all.”

At birth, the child was given the name Paiea – the local name for a now extinct subspecies of soft-shell crabs. The birth took place against the background of unusual natural phenomena – according to one version, Halley’s comet was visible in the sky, passing perihelion in 1758. The priests took this as a sign and predicted that the child would become a great conqueror who would crush all enemies. After listening to the wise men, his grandfather, the ruler of the island, ordered the newborn to be killed “out of harm’s way.” His parents managed to hide the child, and for the first few years of his life nothing was known of his whereabouts. When, after the death of the leader and the next reshuffle in power, the boy was able to return to the court, his name was Kamehameha, which meant “very lonely man.”

Kamehameha the Great Monument in Hawaii. © Wikipedia

Until 1778, the existence of a group of large islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean was known only to a select few in Europe. The Spanish, who traded between their colonies in the Philippines and in the New World, wisely hid their routes from the hostile British. Therefore, there was no written data on the visits of Europeans to the islands, although archaeologists would later find evidence of rare contacts between the local population and the Spaniards.

Read more

Officially, the discoverer of the archipelago was James Cook, who anchored at Waimea Bay on Hawaii’s fourth-largest island of Kauai in January 1778. In 40 years, the Russian flag would be raised there but, in the meantime, the Englishman was extremely happy with his geographical discovery. He dedicated it to John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, then First Lord of the Admiralty and, coincidentally, the inventor of the eponymous snack.

A year later, after an unsuccessful attempt to find a sea route home around North America, Cook returned to the island of Hawaii, where Kamehameha’s uncle ruled at the time. For a month, the British repaired the ship and collected provisions. The crew, which had gone rather wild at sea, began having regular skirmishes with the local population. The conflict ended when the explorer tried to personally capture the chief. In the process, he was killed, his body cooked, and the bones, carefully cleaned of meat, were returned to the ship for an honorable burial. The chief who had evaded the assassination attempt died peacefully a couple of years later, leaving the island to his son and appointing his nephew as the defender of the god of war Ku. However, Kamehameha did not take long to fulfill the ominous prophecy concerning himself. He killed his cousin and became the ruler of the largest island.

Soon, the place attracted enterprising American traders from New England who found out about the archipelago from Cook’s expedition. Kamehameha, who discovered the might of gunpowder after a visit from the British, established sandalwood trade with the Americans in exchange for guns. He then gathered a colossal (by local standards) army of 10,000 people and, in ten years, subdued almost all the neighboring islands with fire and sword, except for the two most remote – western Kauai and Niihau. The Kauai chief, named Kaumualii, was only 18 years old when an armada of 1,500 war boats moved towards his possessions. It seemed there would be no salvation, but the fleet of the mighty conqueror was scattered by a sudden storm. A few years later, Kamehameha began to assemble a new invasion army on the central island of Oahu. Precisely at that time, two ships under Russian flags appeared on the horizon.

(L) James Cook; (R) John Montague © Wikipedia

Fur country

Although Russian research and fishing expeditions visited the coast of present-day Alaska as early as the 17th century, 1783 may be considered the year of the founding of Russian America. This is the same year in which Crimea and Georgia became part of the Russian Empire. By the decree of Catherine II, the American Orthodox Diocese was formed, and the North-Eastern Fur Company was founded. A year later, it established the first permanent trading post on Kodiak Island off the southern coast of Alaska. Initially, it was a private enterprise involving a group of Siberian fishermen. They extracted furs and sent them to Okhotsk, whence the goods were delivered overland to the central part of Russia with great difficulty.

Read more

In 1799, the Novo-Arkhangelsk trading post was established, and Emperor Paul I chartered the Russian American Company. A decision was made not to limit trade to the European market, but to use the Chinese port city of Canton (Guangzhou) and the European trading bases there as the main market. The permanent Russian population of Alaska grew, reaching several hundred families. The Aleuts, instead of resisting the newcomers, began to work for them, learning the language and converting to the Orthodox faith.

From 1790, the senior manager of the enterprise was Pomor merchant Alexander Baranov. But Russian-American company co-founder Nikolai Rezanov wanted to see everything for himself. In 1803, he and a small retinue were part of the first Russian round-the-world expedition led by Ivan Kruzenshtern and Yuri Lisyansky. Ten days after their departure, the head of the expedition was notified that in fact it was Rezanov who had senior authority over the enterprise, sponsoring the entire voyage, and was to be appointed the first ambassador of Russia to Japan.

During the whole journey, Kruzenshtern and Rezanov engaged in power struggles and only the governor of Kamchatka eventually reconciled them on the opposite side of the Earth.

(L) Ivan Kruzenshter; (R) Nikolay Ryazanov © Wikipedia

Sometime before that, the vessels ‘Hope’ and ‘Neva’ sailed to the shores of Hawaii to replenish supplies. The guests were warmly welcomed, although King Kamehameha could not receive the explorers. He was preparing for the second attempt to invade Kauai together with his warriors on a neighboring island and, together with them, was ill with an unknown disease (the campaign would never take place). Russian sailors also visited his rival, Kaumualii, who, being in a hopeless situation, was ready to swear allegiance to the Russian emperor right then and there, just to get military assistance. However, Kruzenshtern had other plans, and the ships sailed further along their routes.

Rezanov was never accepted as an ambassador in isolationist Japan and, arriving in Novo-Arkhangelsk, found the settlement in a depressing state. At the time, all provisions except for fish were delivered from Siberia via Okhotsk by sea, and by means of just one ship. The journey took two to three months. Of course, by the time of delivery, the supplies were far from fresh. It became clear to Rezanov that in order to continue the enterprise, it was necessary to ensure the safety of goods. To this end, he went down the coast on two ships, mapped out a place in northern California for an agrarian colony (the future Fort Ross), and visited Spanish San Francisco, where he made a great impression on the governor, established trade relations, and married the daughter of a local general. The ultimately sad fate of Rezanov is known from the work ‘Juno and Avos’, but his ideas were later used by the “ruler” of “Russian America,” Baranov.

Much was done to organize transit trade with Hawaii. By that time, Kamehameha had stopped trying to land troops in Kauai and achieved his goal through diplomacy – he allowed Kaumualii to remain leader of the island, but on condition that after his death all possessions would go to him as king. Kaumualii could only humbly obey, until one day the Hawaiian gods sent luck right to his doorstep. In January 1815, a storm washed ashore the ship ‘Bering’, which belonged to the Russian American Company. This happened in the bay of Waimea – the same place where James Cook once sailed. Using the ancient custom of coastal law, Kaumualii appropriated the ship’s cargo, estimated to have been around 100,000 rubles. When news of this reached Novo-Arkhangelsk, Baranov set out to reclaim the goods. However, he had neither the strength nor the means to accomplish this. All he had was the doctor.

Read more

The empire of Dr. Schaffer

Georg Anton Schaffer was born in Bavaria in 1779. At the age of 26, he graduated as a surgeon, working in Hungary and Galicia. In 1808, he joined the Russian Army and, after the end of the Napoleonic invasion, he started working for the Russian American Company as a ship doctor. In the same year, on board the brig ‘Suvorov’, he sailed to Alaska, where he decided to go ashore due to a conflict with the ship’s captain. This doctor turned out to be the most educated and reliable person at Baranov’s disposal.

Alaska had no ships that were ready to sail. So, in October 1815, Schaffer, in the company of two assistants, one of whom was Baranov’s son Antipater, sailed several thousand kilometers on an American ship to return a huge cargo seized by a tribe of natives for whom human sacrifices were still the norm. The plan was as follows: The doctor, disguised as a naturalist, was to arrive at the court of Kamehameha, ingratiate himself with the ruler, and wait until help arrived in the form of the Russian American Company ship ‘Discovery’. At the right moment, the doctor would reveal to the king a document showing his real position as a representative of the Russian American Company and the Russian Empire. After that, with the help of the ruler, the plan was to take the company’s property from Kaumualii or get a ransom with sandalwood, load it onto another ship, the ‘Kodiak’ and sail on to China to sell the cargo.

Things didn’t go completely according to plan. Kamehameha’s “advisers” from among American merchants immediately suspected something and warned the ruler to stand on his guard with the Russian German. However, the doctor was able to earn the King’s trust by curing both the ruler and one of his wives from long-standing diseases, for which he was given a stone house in a palm grove on the shore in the area of modern Honolulu. While waiting for the arrival of the ‘Discovery’, Schaffer laid out a garden next to the house and really studied the nature and geography of the island. However, the appearance of the Russian ship once again alerted the king and his American well-wishers, who were afraid of competition.

Georg Anton Schäffer © Wikipedia

The process stalled, and Schaffer considered ‘plan B’. He would sail to Kauai on his own – after all, he already had a ship and all the necessary permissions, so he could even seize the island by force. Imagine his surprise when, instead of long negotiations and resistance, Kaumualii, who had just literally robbed the company, offered to pay compensation for the entire cost of the cargo, recognize himself as a vassal of the Russian Tsar, give the right to monopoly trade in wood, as well as allowing the construction of trading posts and fortified positions on all of the islands. Schaffer, an obviously adventurous and enterprising man, saw this as a great opportunity to expand the company’s territories.

Read more

In May 1816, having consulted all the idols and priests, Kaumuali, dressed in the uniform of an officer of the Russian Navy, personally raised the flag of the Russian American Company next to his family banner over the Gulf of Waimea. The same evening, religious celebrations in honor of the union with the Russian Emperor followed, during which, according to the sailors from the ‘Discovery’, two people were sacrificed. This is the last documented human sacrifice in the history of the archipelago.

The friendship developed at lightning speed. Schaffer was given land on the opposite, northern shore of the island. The doctor named the place Scheffertal and set up the first trading post there, protected from the sea by two redoubts with cannons named after Emperor Alexander and the military commander Barclay. The distillery was one of the first constructions to be built and, later, the first to be destroyed by the islanders. Schaffer named the largest river of the Hanapepe island “Don,” and even christened two neighboring chiefs Mikhail Vorontsov and Matvey Platov in honor of the heroes of the Patriotic War of 1812.

Kaumuali skillfully supported Schaffer’s enthusiasm. After all, he pursued practical interests, which, it seems, the doctor did not realize until the very last moment. A second, “secret” agreement was soon concluded, by which the leader pledged to provide 500 soldiers, and the Russian American Company would arm them with modern guns and deliver them under cover on warships to Oahu and Hawaii in order to jointly retake the archipelago from Kamehameha.

The ruler also proposed to build another fort, this time next to his settlement and from stone, according to all the rules of European engineering with which Schaffer was familiar.

The fort was named “Elizabethan,” after the wife of the Russian Emperor. Fragments of volcanic rock that made up its walls were worn by local nobles and even the wives of the leader, according to local tradition. Schaffer was sure that he was building a fortress for Russia, although for the next half century it was a reliable center of power only for local rulers.

Elizabethan fortress. Bird’s-eye view of the fortress. Reconstruction by A. Molodin and P. Mills, 2015. © Wikipedia

The doctor also bought two American ships in full confidence that his achievements would more than recoup the expenses, and the purchase would be strongly supported by his management. When the former owners of the ships reached Novo-Arkhangelsk and showed the contract to Baranov, he was furious. Instead of returning 100,000 rubles, Schaffer had accrued debts for the company of another 200,000.

The situation began to deteriorate by autumn. In September, Kamehameha – who, of course, was aware of the events taking place with his rival – ordered the destruction of the Russian trading post in Oahu. The matter took a very unpleasant turn in December, when the brig ‘Rurik’ anchored off the coast of Hawaii, making a round-the-world voyage from the Baltic to Alaska and China. Its commander Otto von Kotzebue was very surprised to see 400 armed soldiers meeting his team on the shore. Kotzebue had visited Hawaii as a cabin boy during Kruzenshtern’s first round-the-world expedition and remembered the friendliness of the locals. When he found out that the islanders had been expecting Russian warships promised by Schaffer, the captain was perplexed. He insisted that this was impossible and the doctor, apparently, was acting on his own behalf. Finally, Kotzebue sailed on, without trying to find out what was really going on with Schaffer.

Read more

Sensing that the wind had changed, American merchants from Kamehameha’s entourage began to bluff, threatening to call in five warships. As for Schaffer, no help came to his side either from Alaska or from St. Petersburg. The hired Americans gradually began deserting him, but the doctor did not seem to notice what was happening. What was there to fear? After all, he had a signed military agreement and was the authorized representative of the world’s most powerful country. Everything ended in June 1817, when he and several remaining sailors were forcibly taken out of their house in Waimea, put into a barely functioning boat, and pointed to row in the direction of the no-less battered ‘Kodiak’ offshore.

Most of the crew of the two Russian ships returned to Alaska via passing vessels. Schaffer, as the main cause of trouble, was first to be dispatched towards Macau. Through random acquaintances, he managed to first get to Brazil and then to northern Germany. There, Schaffer unsuccessfully tried to get an audience with Alexander I, who was in Europe at the time, and explain the wonderful promise – perhaps still not entirely lost – of the Hawaiian enterprise. Later, he returned to St. Petersburg, where he tried to persuade the Russian American Company to relaunch the enterprise, but was ignominiously dismissed. Schaffer eventually found happiness in Brazil, where he successfully organized resettlement for the Germans.

The founder of the Kingdom of Hawaii, Kamehameha I, died at a venerable age in 1819. Kuamuali was invited to a meeting of all the chiefs in Oahu, where they forced him to marry his rival’s widow so that his son would inherit the lands. Thus ended the political unification of the archipelago.

© rbth.com

Imperial inertia

The Russian-American Company existed for several more decades but, throughout that time, St. Petersburg considered it more of a burden than a possible point of growth. For the first time, the idea to sell Alaska to the United States arose during the Crimean War. At the time, British and French troops were expected not only in the Black Sea, but also in the Baltic and Northern seas. In such conditions, it was considered impossible to protect several thousand Russian subjects on the opposite side of the world. The sale was carried out in 1867. Within just 30 years, gold was discovered in Alaska and, in another 70 years – oil.

Read more

From far-away St. Petersburg, the idea of overseas colonies seemed non-viable. But, on the other hand, how did the colonies of Spain and Portugal, Holland and France survive for centuries, thousands of nautical miles from the metropolis? Unlike Russian Alaska, most of them sought to become self-sufficient from the earliest days. The leadership of the Russian American Company, however, relied on annual round-the-world “deliveries.” Such a long and expensive logistics chain, of course, could not be justified either from an economic or military point of view.

Following this logic, it becomes obvious why Schaffer was so eager to settle in Hawaii. At the beginning of the 19th century, a geopolitical vacuum reigned in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. British companies had not yet reached British Columbia, the United States would “notice” California only with the start of the Gold Rush in 1837, Spain no longer had the strength to move north of San Francisco Bay. For two or three decades, Russia really had all the cards in its hands but didn’t realize it – or didn’t have the time to capitalize.

The leadership of the Russian American Company received Schaffer’s first reports with enthusiasm. But conveying it to the highest dignitaries of the state proved a lot harder. Chancellor Karl von Nesselrode was skeptical about the idea of acquiring the islands and shelved it. When the proposal reached Alexander I, he considered it inappropriate to create a potential conflict with England or America somewhere on the far side of the globe. It was 1817, Napoleon was only recently defeated at Waterloo, the Holy Alliance was forged, the independence of Greece and control over the Bosphorus loomed ahead. Moreover, in 1816, the Emperor began, as we would now say, “falling into depression.” By all means, it was not the best time for adventures in the Pacific Ocean.

Coincidentally, the “Russian trace” in the history of Hawaii did not stop at that. Russian Narodnik, Nikolai Sudzilovsky, was to become the founder of the Home Rule Party of Hawaii, and the first president of the Senate of Hawaii in 1901. But as they say, that’s another story.

By Anatoliy Brusnikin, Russian historian and journalist